Interview with Zachary Tanner - 2023

Interview #18 (Fiction, Science Fiction, Psychedelic Fiction, Literary Fiction, Erotica, Climate Fiction)

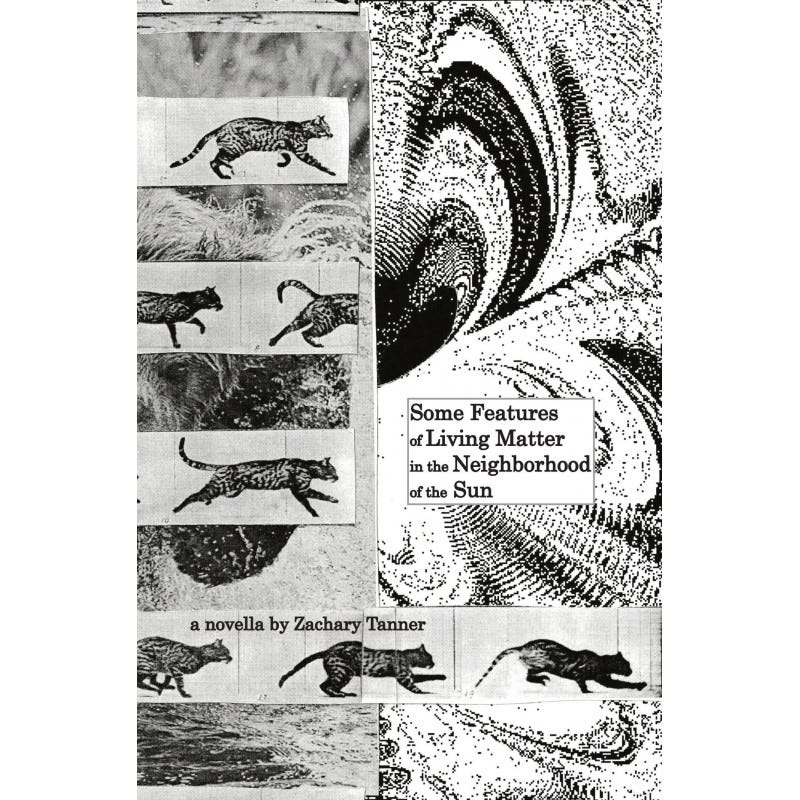

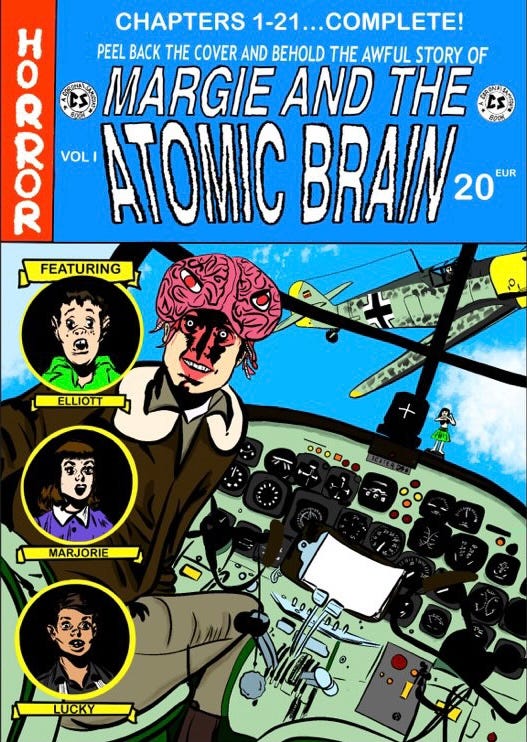

Zachary Tanner (they/s/he) is the author of two published books of fiction, Oskar Submerges (corona\samizdat, 2021) and Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun (corona\samizdat, 2022), as well as the forthcoming 1800-page multiverse novel, Margie and the Atomic Brain, which will appear in three volumes from the same publisher, with the first appearing in early 2023. They have also published several pieces of criticism on authors like Chandler Brossard, Marguerite Young, and Algernon Charles Swinburne. They live just off the Atchafalaya Basin with a spouse and two children.

Randal Eldon Greene: Hello, Zachary Tanner.

The first layer of your Science Fiction novel Oskar Submerges is all about our narrator, Cletus II of Luna, who craves experience and intends to get it by observing the elderly at a brain health clinic on Europa. He's a musician intending to write twelve grand modular synth operas but obtains employment as a janitor in the clinic despite being secretly wealthy. However, this is a book of many, many layers. There's layers of music, a geologic strata's worth of relationships romantic and sexual, and layered identity. Even layers of water within the underwater cities of Europa function as a thematic layering.

There's also layers of psychosis. And it's here where I really want to begin the interview because one cannot read Oskar Submerges without having to contend with the layers of reality, questionable reality, and outright hallucination embedded within the story. Some books like to layer in subtle ways which leave two interpretations available to the reader—I'm thinking of novels like Toni Morrison's Beloved. Your book, however, approaches multiple interpretations by making them real, even when hallucinatory. The need to interpret is there, but the reasons are a real part of the plot and the characters. Cletus suffers from psychosis, having bouts of mania and unreality. I believe he is suffering from bipolar disorder. But Europa is also a hippie's dream resort; drugs of all sorts are widely available and readily consumed. Cletus experiences psychedelics regularly while learning to socialize with the denizens of Jupiter's ocean moon. There is also a native algae species which can bloom and when seen causes a hallucinatory spectacle. The flip side to the algae is that it is also responsible for a disease known colloquially as "french maids," which causes delusions and eventual death when one is unfortunate enough to have physical contact with it (although, to add another layer, it may actually be the parasites in the algae rather than the algae itself responsible for french maids). There's also a species of cephalopod that creates spectacular illusions with its body on a scale beyond human conception and perhaps on the edge of the possible.

When writing Oskar Submerges, I'm curious what tactics you used to keep the narrative grounded while allowing delirium and mania to pull and push and flip entire scenes upside down. And what would you say to a reader who might be a bit hesitant to imbibe your layered prose, fearing an inability to find out "what really happened" as they navigate through an expanding haze of hallucinations?

Zachary Tanner: Hi Randal, what a great question. It's always exciting for me to hear new critical interpretations. I have this memory of working one day on Oskar while listening to Everybody's in Show-Biz by the Kinks, and this verse of "Unreal Reality" really stuck with me: "That house is so big that it reaches right up to the clouds/It's got hundreds of windows so the people inside can look out/Oh, and they look down below and wonder what it's all about." Conceptually thinking about the reader like the people inside the house with plenty of windows that reaches right up to the clouds was the breakthrough, especially once you re-listen to the song and think about this line with the full sonic effect of the electric guitars and brass. I'm not trying to be obtuse, I just found that song really helped me with my final visualization, and the song title is fraught with resonance as far as Oskar goes, and it was by following these sorts of impulsory this-feels-most-natural-for-this-book whimsies that I achieved the final aesthetic effect.

For instance, I first thought of the story while at the bottom of a swimming pool. I then went on to think, what if I wrote a book literally underwater, has anyone ever done that? I would come up for air, go down, visualize the next few clauses of a sentence-in-progress, swim up for air, jot that down, repeat. But that was preposterous, so when I had ideas like that, I would cut them, but for some reason, by that point the swimming pool had to stay. And I think, ultimately, just amassing these sorts of diversions and tangential speculations, I was able to uncover some emergent properties in the book, as if I was fishing them up from my subconscious. I was trying to create the book like a nautilus shell, a series of chambers modeled off of one another growing around a disappearing whorl center. Ultimately, this long period of introspection and germination was followed by the final few years of effort when I forgot all of that and spent my time trying to make it as readable as Virginia Woolf or Nathanael West, paradoxes and all.

As far as readers who would be hesitant to imbibe the prose, sure, that's fair. But do you come back from a mushroom trip concerned with "what really happened?" If you do, you probably don't like taking mushrooms too much, do you? And it's okay if they're not for you. But I certainly like them. Which makes me wonder, is the requisite readerly quality for appreciating this fiction having taken psychedelic drugs and simply being "hip?" I don't think so. My parents like it, for instance, orgies and all, and for context, they raised me Catholic and are in their 60s but had never heard of a "pansexual" before my book, or if they had, they hadn't taken the time to understand what it actually meant. So I have to think there's something creative going on in the book that keeps people interested, even if they come to the book with more conventional expectations of a novel, like a responsible representation of their own sense of morality by the author or, you know, plot coherence, only to have these typical benchmarks of fiction upset.

Randal Eldon Greene: I'm happy that you bring up the orgies. One of your reviewers on Goodreads described reading Oskar Submerges to be "like watching hardcore pornography while listening to a piano recital." In my professional judgment as a bookworm, this is inaccurate. It's much more like watching hardcore pornography while listening to Wagnerian opera. It's grand and dramatic. The music of the novel knocks you back, and the relationships collide with fiery sparks, jump deep into suffocating depth, and melt into painful aria. It's wonderful.

I grant, Oskar leans hard into the sexual scenes. But it's not just sex. It's relationships. In fact, both Oskar and your latest book, Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun, display the complexities of pansexuality and polyamory. For example, there is a character in Oskar named Rosa L. She is described as "a former lover of Ophelia's and a longstanding cohabitant and coparent of theirs [Ophelia and Jose], having birthed two of the seven children." Talk about complicated, especially when you consider the fact that all three of them have both male and female anatomy, and Jose has practiced monogamy with Ophelia as where Ophelia practices pansexuality. To be honest, the amount of drama that ensues from imperfect poly and pan relationships really surprised me. You aren't holding these unions up on a pedestal; rather, you give us a multifaceted view of how this kind of relationship can work both functionally and dysfunctionally.

Zachary Tanner: Thanks for the kind word about my orgies. That particular mean-spirited review from a user with a private profile cut deep. I have my suspicions about where it came from, but I've also a history of paranoid delusions, so I try my best not to think too much about the reviews. But while we're on the subject, I recall another Goodreads reviewer describing it as "sex that made me throb." So, I guess, ultimately, to each their own. And where's the charm in an orgy lacking a bottomless ragtime pianist, even if what they play for the rest of the company while they are fellated is campy or amateurish. I pick up a book that pairs sex and classical music, and I think to myself, yes, this is close to the person I am when nobody else is a round. Even if that comes off as smutty, it's true. As far as I'm concerned, piano music and sex are intercomplimentary sensual delights, and it's almost inhuman to try to debase that.

By focusing on how we relate platonically, romantically, and sexually with any number of people, most of the direct growth that happens is concerned with how we relate to ourselves.

Rosa L.—the character named after the film Rainer Werner Fassbinder was writing when he OD'd—I think it's only natural that Rosa should be someone who actually does vibe pretty well with Cletus; Rosa L seems to have a healthy relationship with just about everyone. Polyamory is a big, tricky semantic game when you get down to it, like identity politics or literature, that has less to do with sex than it does with clear communication. And when I was writing Oskar, I was obsessed with this bizarre and confusing fact of nonmonogamy: that you can have an unhealthy relationship with a person who someone you have a healthy relationship also has a healthy relationship with. It's something that makes polyamorous breakups difficult—if you stop fucking someone that someone you're fucking is still fucking. It just all becomes so quickly introspective and about personal growth is what I'm trying to say. By focusing on how we relate platonically, romantically, and sexually with any number of people, most of the direct growth that happens is concerned with how we relate to ourselves. Workshop why you are drawn to certain people with the people themselves, take some time deconstructing the wild romantic surrogates of one another we create sometimes instantaneously with complete strangers who look or speak a certain way, and you quickly start to uncover personal flaws.

Ultimately, Cletus can't hang because Cletus can't learn to adapt to some of the inherently uncomfortable aspects of nonmonogamy, can't get down the process mechanics of, as you say, "a multifaceted view of how this kind of relationship can work both functionally and dysfunctionally." I wanted to take your typical French love triangle such as Jules et Jim or a more conventional, heteronormative wife-swapping love quadrangle like Hawkes The Blood Oranges, and add a dimension, ask myself what it would look like if it was some kind of gay love tesseract, and what I ended up with was Oskar Submerges, and I'm proud of it as a work that does justice to the vertiginous social dysphoria of first-time nonmonogamy.

Randal Eldon Greene: I love how so many of the characters in Oskar Submerges are artists. Some are struggling horribly to even get started, such as Cletus, our narrator. Oskar, on the other hand, lives fully in his creative life, painting away whole days and sometimes weeks. Though by trade he's an architect who hasn't really ever seen any of his designs built. There are musicians performing in multiple bands, cutting records, playing gig after gig . . . but they're not rock stars. And then there's my favorite artist, a writer—the prolifically published Agostinelli who, despite his prolific literary output, makes a living as a bartender. All this causes me ask, what realities of the creative life have you experienced which made you develop such dynamic artists for your novel?

Zachary Tanner: I had a long first run for about 8 years of writing fiction for 5-8 hours a day, every day of the year, even holidays. During this time I worked odd jobs as a valet, a production assistant, a pizza-slinging fry cook, etc. My philosophy was I had jobs that paid the bills but were part time enough to keep me writing and reading and going to the university library almost all the time, which was my idea of how to get started writing novels after deciding not to pursue a creative writing MFA once I'd earned my film baccalaureate.

It was during this intense disciplinary period that I started writing Margie and the Atomic Brain, and completed the first, 2,131-page typescript between March of 2015 and December of 2017. So, by 2018, when we unexpectedly were expecting our first child, I had a crisis trying to adjust. There was all this momentum, a whole method for writing I had to scrap, learning to work instead in little breaths whenever the kids are napping or sleeping for the night. But I think this adjustment at the end of my Outliers-esque apprentice period was the catalyst for some of those more outlandish artists in the books. I had developed a highly idiosyncratic method and obscure origin story for myself that had to be scrapped when the becoming of parenthood force-fed me a personality metamorphosis. It was looking back on how serious about the art I was before I kind of let go of all of that that made me want to write those characters. I didn't have to waste a bunch of years crafting an obscure story for myself when I could just craft one complex world with all kinds of fun origin stories that eventually borders on being an encyclopedia of ways to be creative. Similar to how you mention the relationships functioning.

In my early 20s, I was also very concerned with this cynical view of how horrible it was that everyone I knew was some sort of artist. It was often alienating for my partner, who didn't practice art and felt uninteresting to those despicable types of people who use artistic talent for social capital. So in a way it is also, I guess, a joke about pretentious art and artists. The least they could do would be to take after any of these Europan panfilos, who spend almost all of their energy on their own art, and yet can still recognize and appreciate beauty when they see it.

Randal Eldon Greene: Cletus's friend Oskar is a centenarian who is sliding slowly backwards into reverie. His art often reveals a deep, deep love for his wife of former years. And yet this love is stained by a horrible gash—one which he maybe had let go of. But as dementia or a complication of renascent french maids symptoms deteriorates his faculties, all the pain of betrayal crashes over him as if it only happened yesterday. Did you know someone like Oskar who suffered from age-related dementia? And one thing I need to search for in my next rereading of Oskar Submerges is why Oskar asks Cletus to be the one to help him escape the pain of memory. Or perhaps you'll be kind enough to offer us a hint?

Zachary Tanner: My Great Aunt Mary was the closest hit, but there have been several. And I think that's an easy question. Cletus is the only one foolish enough to do anything Oskar says, he's so impressionable, and really Oskar has given him a lot in terms of social set and setting. In Oskar's eyes, it's really the least he could do if he cares for Oskar like he says he does. If the love is genuine, what favor is too big to ask of a true friend? I don't think there is one.

I think something interesting though is we're using pronouns here to describe these characters like he and him, and never once in the book is Cletus or Oskar or any other one of the living characters described by traditional, gendered pronoun structures. As far as I know, the only pronoun-gendered character in the book is Oskar's deceased wife Olivia, now that we mention her, who is, as I take it, a trans woman.

Randal Eldon Greene: Interesting indeed, though I'm certain I started it. It's difficult for me, who only has one person in his personal life who does not use typical pronouns, to not assign classic gender pronouns to characters even when they were written with gender neutral ones. Or perhaps I noticed while reading the novel but it slipped from memory, though I don't recall pronoun choices causing me a bit of confusion while reading Oskar Submerges. I'm actually glad to know that you had Cletus use the same pronouns as all the other characters, since Cletus is the sole character I can think of who has only one set of sexual organs (which is what makes Jose so attracted to them).

I did noticed that in Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun the character of Poppy uses they/them pronouns. I feel like this latter book could be in the same universe, just set earlier, when colonies on the worlds around our Sun were first being established. It's never stated explicitly, but is Poppy supposed to have the same kind of multiplicity in regards to their physical sex?

Zachary Tanner: The whole idea with Oskar was not to use neutral pronouns but to structure the language without the use of pronouns. We were going to print about a year after I myself had begun to consider myself nonbinary after religiously reading Donna J. Haraway. In those last few drafts of the book, I took everywhere where there were original pronouns and cut them, and then tried to restructure each sentence so that you couldn't tell that anything was missing and see if I could still have it all read cleanly in an entertaining, page-turning fashion. I guess that's the most experimental thing about the book. Keeping Olivia's she/her pronouns in light of that endeavor is an ode to some of the beautiful transgender people I've known and befriended in my adult life.

With Some Features of Living Matter you've got something much closer to our own world. You're not the first reader to suggest that the two may be in the same alternate history timeline. My partner, for one, wishes I had put some sort of Easter egg in there to satisfy readers that they ARE connected. The way I see it, sure they're in the same literary universe, because of the millions of pieces of fiction that have ever been written and printed, they are the only two that I've published, so that's like being in the same universe, I guess, looking at things cosmically. Or maybe, it's like all the author's are suns, and these two books are in my solar system, but the way I see it every human in every piece of fiction that has ever been printed technically coexists in the same universe as all the other characters in all the other books humans have written. There is only the one universe, which maybe exists in a matrix of multiverses, and all of us humans, even the authors, share it, no matter how convinced some may be that they're out here Making Entire Universes. But I digress, what I meant to say about Some Features of Living Matter is that it was written to be read as a 2050 Climate Crisis kind of book, even though by my interior reckoning it probably happens sometime around 2090, for these are post-climate characters.

I remember when I was trying to envision 2193 for Oskar, I was working backwards, and I think the colonization of Mars was much closer to something like 2075, which maybe that lines up, but also, the Mars concept seems to be an endeavor in its infancy in the novella, whereas in the novel I kind of pictured you know, a sprawling colonization having already happened by then. But wait, what did I mean to say?, oh yes, Poppy definitely doesn't have a multisex configuration, if that's what we're uncovering. Even if the stories are related, that's something that happens much later on Europa, at least the normalization of it. I don't know about Poppy's physical sex, but if it's worth anything, their mom Myzee I read, again, as a trans woman who had a transition some time after having children.

Randal Eldon Greene: I did notice that one could read Some Features of Living Matter as a Cli-Fi book. I actually learned the term (which is short for Climate Fiction and tends to be associated with speculative stories) when the publisher of my first book realized that they had allegorical Cli-Fi on their hands. While I think it's not only inevitable but imperative for authors to pay attention to the world around them and write about the issues of the day, I will admit to getting into a slight disagreement at a writer's conference with a graduate student who was taking a class focused on Cli-Fi. She was telling me that Jane Eyre is Climate Fiction because there's a scene where a tree gets struck by lightning. I had read the book less than a month before and knew that the death of the chestnut tree was an omen about Jane and Mr. Rochester's ill-fated engagement and had nothing to do with environmentally-focused fiction. Your book does more than set itself in a swamp and have a storm blow through. Explain how Some Features of Living Matter addresses today's Climate Crisis through its fictional narrative.

I'm also wondering about your thoughts on fiction that tackles the topics of its day being labeled with things like Cli-Fi?

Zachary Tanner: I like the way a couple of my first readers of that book have put it. My publisher, Rick Harsch, said it presented a horrific climatic event with a durable human response. My editor and wife, Amélie, said it's bleak, but not completely without hope. I look to the title and think that it's me as a creative thinker just trying to sum up in 90 pages what's at stake, what in this solar system seems to me after almost three decades as a human being to be a handful of things worth living for that would be lost if we all died.

Cli-Fi sounds ok. Part of me wants to be cheeky and own it. I'm more wary of graduate students and writer's conferences than I am of labels like New Wave Science Fiction or Speculative Fiction with a capital SF. If I look at the work through labels, maybe it's interesting to first come out with a pornographic musical and follow it up with a piece of sentimental Cli-Fi. Hmmm, maybe another label for Oskar could be Clit-Fic?

Randal Eldon Greene: You make a good point. Although in Oskar, there is a lot of focus on the environmental degradation wrought by humankind on an alien world. Europa's native inhabitants were especially impacted with many of the species going extinct. It's the age-old story of human colonization.

There is one character who is leading an initiative to try and preserve some of Europa's animal life: Dr. Plasma, director of the Nautilus research station. Is Plasma a mad scientist, in the vein of Dr. Frankenstein? Or is the doctor a grand and tragic hero ripped from the decks of the Pequod or perhaps plucked from the ramparts of Elsinore? What I do know is that Dr. Plasma gives rise to my singular complaint about Oskar Submerges: I want more Dr. Plasma. He's so charismatic, eccentric, and visionary. What can I say besides, "I'm a Team Plasma fanboy!"

Zachary Tanner: I haven't gotten much feedback about Dr. Plasma or the Nautilus initiative or the eleventh dimensional fairies or any of the aspects of the book that I see as most metaphysically far-reaching, so thanks for saying so. Most readers seem to latch on more quickly to the musical structure or the transgressive body politik of the thing, and it often sounds like either of those two thematic leitmotifs together are enough to get most people through the book. I really wonder if a reader who actually believes in Terrence McKenna's DMT fairies (I guess I kind of do? I believe in ghosts...) will come along and unpack the second half of the novel, which most people seem content to pick up and admire like a shell on a beach and then toss back down and keep walking. I'm convinced if you really tried to unravel it all, Plasma's monologues and revisiting what's said in the early chapters about 'french maids,' you've got to realize are both maps to understanding the hidden transcendental structure that sets up Part III and the elusive collapse of events that serve, I think quite nicely, as an ending. They were heavily inspired by Dr. Frankenstein, sure, but also some of my other favorite fictitious doctors like Djuna's Dr. Matthew O'Connor or Burroughs's Dr. Benway or maybe Dr. Morbius from Forbidden Planet.

Randal Eldon Greene: During the second half of Oskar Submerges, I began to realize that this novel was high-density and would require some rereading. DMT fairies—the linguistic elves to be glimpsed behind the veil of our obscuring reality—are something that has long fascinated me, so I'm excited to know that they may be more integral than I initially realized. I think on my third go at your book, I'll start at the end and loop around to the beginning.

There are multiple covers for Oskar Submerges. I ran across a picture of Oskar on Instagram and ended up purchasing it and a few other corona\samizdat books. The copy of Oskar sent to me happened to be the one I saw online, though I'd love to someday collect all editions of your novel. They just look so damn cool! So many of corona\samizdat's books have amazing cover art. To me, that's half the appeal.

If I'm not mistaken, you design a lot of the book art for corona\samizdat. Tell us about the artwork for Oskar. How did you learn to create book covers and how did you land a job with this small, but absolutely fantastic, publisher from Slovenia?

Zachary Tanner: Well, I think it was around the time I ordered a copy from that first big batch of The Manifold Destiny of Eddie Vegas editions to go out during the first month or two of quarantine, the ones that got lost on a boat in the Atlantic for three months during the early pandemic, and did not arrive until some time in June of 2020, though they had been ordered in March. Thanks goes to Chris Via's youtube channel Leaf by Leaf for bringing Eddie Vegas to my attention.

In some form or another, I wrote Rick a message that ran along the lines of "It's wild you went to the Iowa Writers' Workshop, because I actually am interested in reading your work." This was while I was waiting for my Eddie Vegas. Then, after it arrived, I started reading Eddie Vegas on a little plywood loft in my metal shed in Louisiana in the middle of the summer during a rough patch in my life, and was really taken with it, and I was struggling with alcohol, and Rick sent me a copy of Arjun and the Good Snake: Being an Ophidiological Account of Six Weeks in India without Alcohol, which was a pre-corona\samizdat Slovene English language hardcover edition, and it really helped me on my journey to, at the very least, alcohol regulation. And when his publisher for the reissue fell through, he needed a cover for the corona\samizdat edition, and at this point, since he had sent me the nice gift and I liked the book, I finally told him I had done graphic design-like work before, and that's how I started the covers. I wouldn't call it a job. That implies there's any real money to be made in the aesthetic enterprise of 21st Century fiction. Or that I want to make any money from this. Or that I do actually make some money from it. I'm just glad the books exist and in their existence help more books from the press to exist in the future.

The artwork for the original Oskar I made in my shed with barbasol and food dye and a handful of found objects. The newer edition has two versions of a painting by a friend of mine, an artist from my town, named Kamille Taylor.

Randal Eldon Greene: There's rumors floating around in our neck of the social media sphere that you're working on a big book. Care to tell us a little bit about it?

Zachary Tanner: Big book, yes: Margie and the Atomic Brain, Volumes I-III. It's an 1800-page multiverse novel that's forthcoming from corona\samizdat early Spring of 2023. I've been writing it since March of 2015, though for several years I put it down and was busy settling down and having children and writing Oskar Submerges and failing to get published with the intention of publishing some other material so that by the time I was finished with Margie, at least somebody might know something about my work.

I failed to get published until I met Rick, but from the beginning of our friendship, he has been devoted to helping me find a way to prepare this thing for print in a realistic way. At first we talked about doing the six books in pocketbook, but that would have been 60 EUR for the whole thing, plus shipping every six months when a volume would come out. It was a fun idea to think of serializing it like that, but ultimately it seems most feasible for the press to bring out a 725,000-word novel as three large-format paperbacks. It'll still be 60 EUR, but spread across several years, and when one does order a volume, a nice thick doorstopper will arrive, and just think what the three of them will look like sitting uniformly on the shelf, ahhhhh. Hopefully, one-day, we will be able to print all three in one big book, by basing the print run off of pre-order numbers, but that's several years down the line. The first book is out in the next six months, but the third volume likely won't be finished until 2026.

The story is my attempt to situate fully-developed characters believably within a schlocky 50s B science fiction uni-/multi-verse. I was inspired by movies like The Brain that Wouldn't Die, The Brain from Planet Arous, and Donovan's Brain, which are all pretty campy looking back on them, but I thought there was this potent, untapped metaphor if one would use fiction to explore what exactly the consciousness of one of these villainous super-brains was like. It's a trope, sure, but one that had never been explored and drawn in its full poetic potency by cinema because of certain limitations of form and industry, one that I thought I might like to tackle in a serious way in a gigantic mega-novel.

Randal Eldon Greene: Now this question is of personal interest to me, what's your secret to writing while also being a parent?

Zachary Tanner: I have no secret to this. I often complain that I wish I had never begun writing as a teenager, because it's just too damn difficult to try to be a well-meaning, functioning person with kids (mine are 1 and 3, and I'm a stay-at-home parent, so, yeah, no time to be a person) and keep writing creatively. I get through it by letting this feeling melt and reminding myself Dr. Johnson wrote that he only needed two or three hours a day over a specific period of months to create his Dictionary of the English Language. Diana Gabaldon has some excellent writing about this in her Outlandish Companions. I really get frustrated sometimes, and when you add home renovations on top of it all, I'm quite prone to panicked breakdowns. If I give off the impression that it's easy, come spend like . . . three days at my house. It's not easy, it's not rewarding Writing Fiction, and there is little of the immediate connection you get with your audience in forms like Music or Painting. It's quite an abysmal enterprise, and to do it with children is just masochistic.

I'm thinking of taking a six-month Sabbatical after Volume One, but that's the thing, will I be more miserable if I don't write? Probably. But most days I feel like I can't sustain this. My kids will be older one day, I know, and there will be more time, but trying to juggle the two has really limited and bastardized any literary ambition I ever had. I have to remind myself Proust says something like writing a book is a noble endeavor even if it's a bad book, because it is a noble thing to do—to write a book.

I don't like writing, but I'm a creative person and started doing it young and it comes naturally to me, so there's more of an immediate reciprocal energy as an artist, that is I can say what I want to say in fiction more precisely than I can say what I want to say with music, and I guess I stick with it because I really want to finish Margie and the Atomic Brain, but ask me any random Tuesday and I'll tell you I'm never writing another book after Volume III. Then I get on my zero turn mower, have a thought for what the next book could be, and only time will tell if I do or not. I'D RATHER BE STUDYING UPRIGHT BASS is my secret to effortless integration of the fictive enterprise into my personal life. It's certainly not my priority, but I can't stop doing it.

Randal Eldon Greene: You mention that lack of immediate connection with an audience that comes with writing fiction. I feel like this is certainly the experience of most authors. Who is your audience? How are you finding readers?

Zachary Tanner: I think Stanley Elkin said he knew all his readers by name? I find readers by knowing people as a coagulate mass of cells known as Zach Tanner, and in being Zach, sometimes I hear that someone has read the books or one of the books. If they have anything to say at all, it is either so positive or so cruel and negative, I remember them by name, so I think the same is kind of true of my audience. Sometimes it just isn't for them, which is fair. Like we said, maybe mushrooms aren't for everybody. I want readers to be comfortable with what they're getting themselves into, so there must be the performance of some kind of persona at play, but I try not to think about it too much. I'd much rather think about the books I'm reading. It is increasingly rare that anyone who a) doesn't know me independent of my literary pursuits or who b) is not an aspiring fiction author who takes it into their heads C\S might be just the press they've been looking for expresses any interest in my work.

But of course I'm thankful for all the nice things people have said. I think I'm just a little cynical about it as a way to not think about it and keep working. In an ideal world, I'd throw a party for all my readers, so I think I have some complex feelings on the matter. My partner, Amélie , has been my first reader for everything for the 9 years I've been writing, though, ever since I started taking it seriously. She also pays my rent. So it goes.

Randal Eldon Greene: I'd attend that party! Having a supportive spouse is, in my experience, important too. How would you say your partner has helped shape your books?

Zachary Tanner: Amélie is my wife, partner, best friend, coparent, the love of my life, my agent, manager, distribution specialist, the dedicatee of basically all my novels, occasionally my social arbiter, a pragmatic, empathetic intercessor, and an essential collaborator. It's one of those literary marriages like Catherine and William Blake or Véra and Vladimir Nabokov. She edited the novella, and she's lined up to edit all three volumes of Margie and the Atomic Brain.

Randal Eldon Greene: Well, I'm looking forward to reading all of your future books. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions, Zachary. It was a pleasure.

Purchase Oskar Submerges here.

Purchase Some Features of Living Matter in the Neighborhood of the Sun here.

© 2023

bio photo by ALEX BAUDOIN

About the interviewer:

Randal Eldon Greene is the author of Descriptions of Heaven, a novella about a linguist, a lake monster, and the looming shadow of death.

His Instagram is @RandalEldon Greene

His website is AuthorGreene.com

You can also support our work by buying cool merch like mugs and t-shirts.