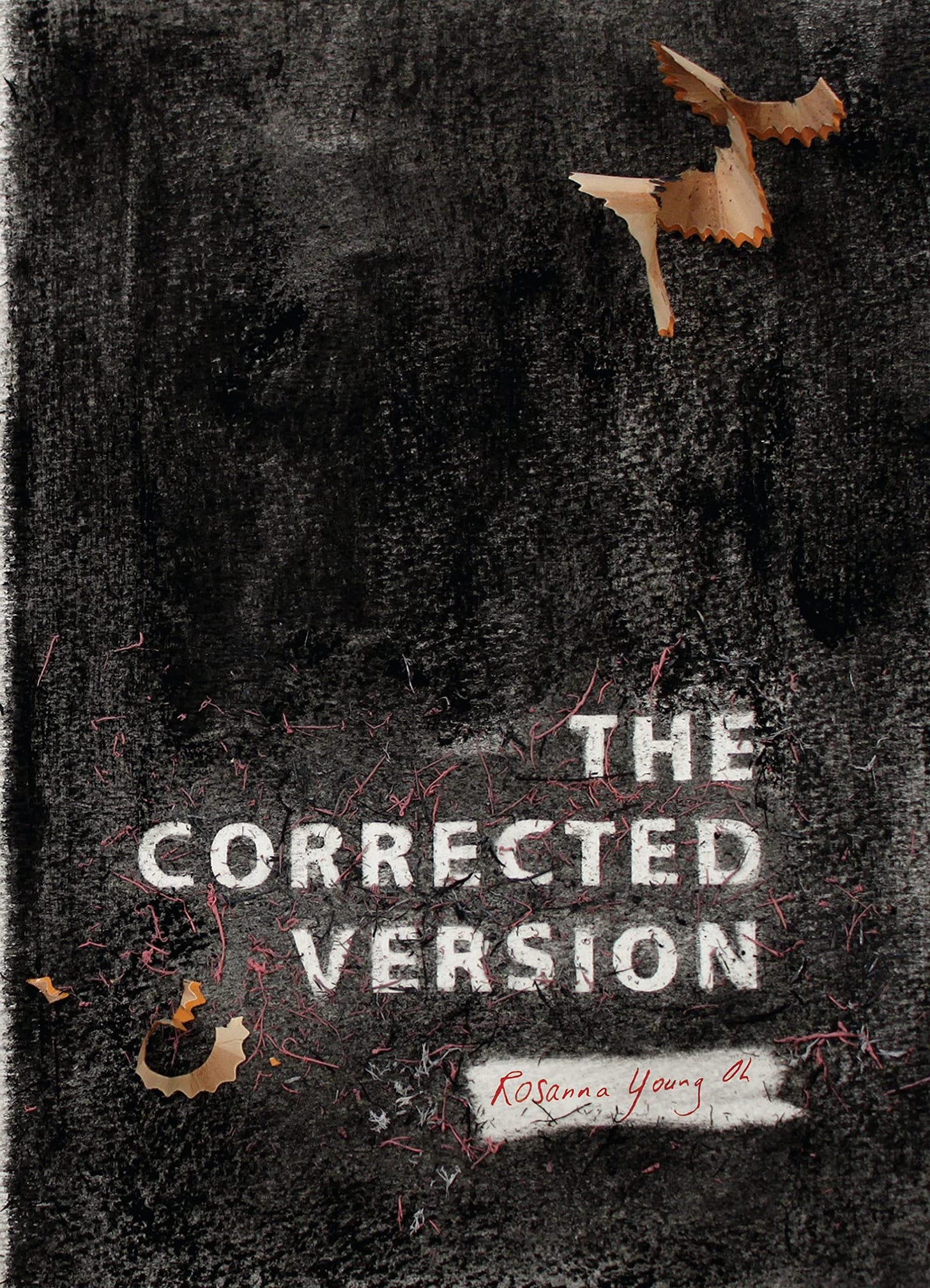

Rosanna Young Oh is the author of The Corrected Version (2023), which is her debut collection of poems. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Literary Hub, Best New Poets, and Harvard Review Online, and has received honors that include scholarships from the Sewanee Writers’ Conference and New York State Writers Institute. Her poetry was also the subject of a solo exhibition at the Queens Historical Society, where she was an artist-in-residence. She currently lives and writes in New York.

Randal Eldon Greene: Hello, Rosanna Young Oh.

You’ve written a beautiful collection of personal poems, and they were very touching. Creating a collection that coheres as well as the poems in The Corrected Version is a process of culling what doesn’t belong and matching up what does. You’ve had poetry appear in many publications, so I’m curious what the process of deciding what belonged in this book looked like for you in a practical and in an emotional way.

Rosanna Young Oh: Thank you for reading, Randal, and for your kind words. My process was mostly trial and error since I didn’t set out to write this book; it simply grew, poem by poem, failure after failure. Some poems I knew belonged in the collection from the beginning. But I threw out poems, even those published in journals, because they didn’t contribute to what was ultimately the book’s arc. Once I saw the arc, I also saw the gaps in the manuscript. I spent a year or so writing and adding poems.

Acknowledging that I didn’t have a cohesive collection was humbling. Since writing many of the poems took long enough—the oldest poems are fourteen years old—I found the prospect of having a less-than complete collection disheartening. But I put my ego aside and got to work.

Randal Eldon Greene: Your parents both loom large in these poems. In fact, you dedicate the book to them. So tell us a bit about your parent’s background, where they came from and what they did for a living, what they were like as people.

Rosanna Young Oh: Yes, I am very close to my parents, who immigrated to the U.S in the late 80s. I inherited my love for books from my father, as well as a love for history. He is also unique amongst his peers for encouraging his children to be well-rounded. He was proud to take his family to Broadway shows and expose us to as many cultural experiences as he could afford.

My mother is the maknae (or the “the youngest child” in Korean) in a family of six children, and she’s the only one who lives in America. When I returned to Korea in October 2022—my first trip in over 20 years—I was struck by how her older siblings doted on her as the maknae, since she has always been the strongest person I know. She is the heart of our family, the peacemaker. In another life, she studied art.

My parents have run their small business, a grocery store, for more than thirty years. They are incredibly hard-working people with spines of steel—not unlike many working class Korean American immigrants in New York. They are affectionate, generous, and funny, too. I have many memories of family gatherings that are filled with food and stories. I know that they would do anything for my brothers and me, sometimes to a fault.

Randal Eldon Greene: One of the motifs you use in The Corrected Version is that of food. For me, the fruit and the fish you describe paint the environment of the Long Island grocery. Reading your poems, I could almost smell your parent’s store!

Rosanna Young Oh: Yes, place plays an important role in the book. Dave Smith, my M.F.A. thesis advisor, would ask, “Where’s the movie?” during workshops of my poems—many of which were disembodied lyric poems. You couldn’t tell who the speaker or subject were. Up to that point, I hadn’t written much about my parents’ store, probably out of self-consciousness. (I’ve attended elite schools where not many people in workshop looked like me.) Professor Smith challenged me to think about place, which opened my poems up to more possibilities.

Randal Eldon Greene: One of the sadder poems is The Gift. In it, a customer says, Give this garbage to your children, and hands a rotting mango to your father, who then tells you it’s not a gift. But you wanted that mango, knowing it’s sweetest when it looks half-rotten. But your father won’t share it. He ends up eating it himself. Why do you think he chose to withhold the mango from you?

Rosanna Young Oh: My father is a complex man with deep feelings that took me decades to appreciate. Even now, I remember just how upset he was that a customer—an old white man—had insulted his children, suggesting that we were worthy of eating only garbage. For me to eat that mango, as ripe and delicious as the fruit was, would be to realize the customer’s insult. In the poem, the father eats the mango out of self-sacrifice. In a way, he swallows his pride so his child will not.

Randal Eldon Greene: The theme of jobs—of running a business— isn’t one I see a lot when reading poetry. Do you think your poems explore this theme because it was so much a part of your life growing up or is it maybe a way to honor that kind of hard customer service labor which, as an adult, isn’t quotidian for you anymore?

Rosanna Young Oh: I love this question, thank you so much for asking it. Yes, labor was part of my childhood and writing poems about it was a way for me to honor the working-class communities I grew up in. Again, it took some time for me to write so openly about my experience at the store. Retail work and manual labor are a reality for so many Americans that it’s strange that we’re not writing about it more in Poetryland.

In college, I thought that the attitude towards manual labor from both professors and peers could be snobbish, as though any job that wasn’t intellectual was less-than. To this day I can’t forget a Yale classmate’s words about another Yalie: “Her father is a PLUMBER!” Her voice dripped with condescension. I had professors, too, who loved poets like Whitman and lectured on the ideals of a democratic America but didn’t seem to understand why I was so anxious about my post-graduation life, or what it’s like to not do what you “love.” Writing about labor is my contribution to a conversation that I hope will continue.

Randal Eldon Greene: While I’m certain you encountered some goodhearted people and brilliant professors at Yale, do you ever regret not attending a less prestigious university?

Rosanna Young Oh: I don't regret attending Yale because my writing life started there, and it gave me friends for life. (Also, I've found that regrets are bad for my mental health.) Yale was not easy for me, and as a first generation-college student, I do wish that I could "redo" Yale sometimes. The ongoing conversation around access to resources and privilege that has happened within the last few years is one that I hope will lead to meaningful change.

Randal Eldon Greene: There’s a line in “Medusa” where you write I am my father’s daughter. You are talking about your hair, which the women in the salon your mother goes to believe needs straightened. But throughout these poems, I see you identifying with your father in myriad ways beyond similar hair. He’s not a stranger to you in the way some fathers can be strangers to their children. He’s a reader of poetry and was even a writer once, before you were born.

Rosanna Young Oh: I wanted to capture the culture of the Korean American hair salons that I frequented in Queens as a child with my mother. The ajummas would almost always make deductions about my personality and parents from the state and quality of my hair. I had frizzy wavy hair diverged from straight hair, which is the Korean beauty standard. Many ajummas suggested that I straighten it permanently. To me, that suggestion seemed very gendered and kind of othering. Nowadays, the ajumma at my salon forbids me from straightening it.

Randal Eldon Greene: For me, “The Problem with Myth” is the central poem of The Corrected Version. In it your mother relates a myth about an angel whose wings are stolen by a woodcutter who then rapes her and, like in so many old tales, marries her. But your father provides a corrected version, one where the woodcutter is seduced. Her beauty justifies his actions.

This poem is, of course, about more than a myth. It’s a poem about the central issue in your collection: the story we tell about ourselves versus the story others tell about us.

Rosanna Young Oh: “The Problem with Myth” isn’t about my parents, but I’ve found that parents provide a natural and compelling framework with which to explore the stories we inherit and that we continue to tell.

Throughout the book, I play with the idea of storytelling—is it just truth-telling or is it more artful than that? Why does it matter to the speaker? I’m also attracted to the idea that we actively choose the stories we believe, and that our lives reflect this process.

Randal Eldon Greene: You write about a kind of anxiety that someone in the modern world can feel. It’s a complicated anxiety and one I think needs poetry. (Then again, I think many human experiences need poetry as a path of contemplation.) “Feeding the Koi” really explores this complex state of anxious uncertainty.

In this poem you’ve turned 34, your friends are starting families, and you’re wondering if you’re returning home because you’re

a dutiful daughter

or coward, whether returning

to Jericho would make a mess

of everything.

Fear had carried my life,

and I was still afraid.

As I scattered pellets

into the dark, the koi shot

beyond the floating plants

to where the food fell.

Later, from my bedroom window,

I watched the moon set

with my heart in my mouth –

its longing, a tenderness.

The koi move from the darkness of uncertainty to the pellets of food because like your friends, they know what they want. The moon—a feminine symbol and a symbol of change—is disappearing from sight, the antithesis of your unchanging fear, a fading image like the novel possibilities of what could have been had you known what you wanted; instead, you choose to return to Jericho, New York, still afraid and not truly knowing what it is you want.

I think this poem is a beautiful illustration of how the anxiety of our own freedom can actually trap us, keep us from moving forward.

Rosanna Young Oh: What a thoughtful and beautiful reading. Thank you. We’re living in a world of chaos, of extreme contradictions. The poem is both a record of time passing and a “momentary stay against the confusion of the world,” as Frost puts it. The koi from the Chinese legend is a Sisyphean figure that swims up a waterfall before successfully reaching the top. The speaker’s koi circle in a manmade pond that doesn’t belong to her.

Randal Eldon Greene: Death has made spendthrifts of us all — / even the truffle oils have sold out. These lines come from “Hard Labor,” a poem about the pandemic. Your father got COVID and was hospitalized. How did having to work in his stead at the store change the lockdown for you? Was poetry even possible during this time?

Rosanna Young Oh: That was a character-building time. For me, I need some distance from an emotionally charged event before writing about it. I wrote my first draft of “Hard Labor” in spring 2022.

The lockdown made clear the classism that undergirds our society. Some of us can afford to work remotely (myself included, though that wasn’t the case until after lockdown started), some of us cannot. I was the only one in my friend group whose parents had to risk their lives for their work. During that time, my mother and baby brother were also sick, and my other brother, a Marine, was stationed in South Korea. I had a full-time job in the pharmaceutical industry, which was undergoing unprecedented growth and change.

So you can imagine what my days looked like: grinding out marketing collateral and being “on” in virtual meetings at work; calling the hospital during every shift to speak with the doctors and nurses; checking in on my mother and baby brother; updating my other brother and the rest of the family with news; dropping food off at the hospital for the staff; managing the store; worrying about job security, etc.

Poetry was not possible. My entire brain was focused on keeping my family alive or preparing for the worst. I wanted everything to end. Somehow it didn’t. I’m indebted to my network of friends and extended family for their support during those early, scary days of the pandemic.

Randal Eldon Greene: Death—or more specifically, time and its incessant ticking—is brought up in multiple poems. There’s your mother’s gray hair in an egg, villagers speculating about the afterlife, a poem about your grandmother’s passing in “Three Women,” and plenty of other instances.

I would not describe your poems overall as memento mori, but when I do see death or reminders of the shortness of life in your poems, I find myself wanting to accomplish more, to close my apps and get to work. The way you explore death in your poetry makes me think maybe this is purposeful, as if you intend for your poetry on aging, morbidity, and death to motivate your readers to start living now.

Rosanna Young Oh: Yes, life is short. A career is shorter. I’ve been told that I put a lot of pressure on myself by more than a few people, including my father and brother (the Marine)—which is saying something.

The reason for this urgency probably arises from childhood. I’ve always wanted to make my parents proud before they die. I’ve also seen several of my parents’ peers from the Korean American working-class community work themselves to early deaths. So yes, I’m hyperconscious of the fact that life is short.

I’ve also learned the hard way that things happen on their own timelines, including books of poetry. When I was younger, I wanted so badly to be a poet who mattered. Now I live a little more mindfully and more gently because some things are just out of my understanding and control.

Randal Eldon Greene: Some people think confessional poetry is easy because you’re just writing about yourself. But when done right, confessional poems explore the universal through the personal. I think you’ve done that rather well here in your confessional pieces.

Rosanna Young Oh: Thank you! My use of the confessional in certain poems, like “Hard Labor,” is intentional. I found the lyric I to be the most efficient voice for communicating the full spectrum of emotions felt during the events captured in the poem. Knowing that the events are happening in real-time to the speaker seems more impactful than a recounting in third-person.

Wordsworth is the first poet who taught me to explore the universal through the personal. I devoured his Lyrical Ballads after falling in love with the Romantics. A poem like “We Are Seven,” for instance, is a meditation on death and family as well as a narrative, which is more profound than is apparent. Whenever I use the lyric I, I do so in search of something greater, of the unsaid.

Randal Eldon Greene: You’ve also made clear in the course of this interview that not all characters in your poems are real—some are fictionalized. This reminds me of some of my favorite Allison Hedge Coke poems. Does it matter to you that readers, like myself, may not be able to distinguish your real life (as put in a poem) from your purely poetic fictions? And do you think readers in general should be more cautious about approaching poetry like yours as wholly nonfiction?

Rosanna Young Oh: This is a great question. It's understandable and, even inevitable, for a reader to approach my book as an autobiographical work. But what is lost if the book is read as purely nonfiction? The speaker is also thinking about art and artmaking, labor, the pandemic, and, sometimes, her imagination takes over. There is more to the book than the speaker's Self.

Randal Eldon Greene: Who were your mentors and what authors inspired you?

Rosanna Young Oh: In college, my mentor was Louise Glück. In my M.F.A program, my mentors were John Irwin and Dave Smith. As a student of the Western canon, I can list so many influences: Charlotte Brontë, Jane Austen, Shakespeare, Donne, Milton, Wordsworth, Whitman, Dickinson, Cavafy, Robert Hayden, Yeats, Seamus Heaney, Roland Barthes, etc. If we’re talking about contemporary writers, then I’d say Jack Gilbert, Anne Carson, Sandra Lim, and Yoko Ogawa.

Randal Eldon Greene: As a Korean American, do you ever feel pressured to write about identity? Or is there something about the U.S. that makes it a necessity to explore identity through your art?

Rosanna Young Oh: Yes, I have felt pressured to write poems about my Korean American identity more directly. But I didn’t start writing poems thinking, “I must write Korean American poems.” (What does a Korean American poem look like, anyway?) I started writing because I fell in love with the English language and its possibilities. Whether or not I write directly about my identity, I trust that I’m a Korean American writer.

Randal Eldon Greene: I have some Korean relatives, some here in the States and some who live in Korea. Do you think your book will be translated for a Korean audience at some point? Is that something you would want?

Rosanna Young Oh: Interesting question! I would be open to the idea. And even though I write primarily in English, I think there’s something Korean about my sensibility that isn’t readily apparent in the language itself. For example, tone and image.

My family in Korea would be thrilled. It would be interesting to learn what they think of the book.

Randal Eldon Greene: Do you write poetry daily? Novelists like myself often set ourselves a weekly writing schedule. But I’m wondering what your process is like.

Rosanna Young Oh: I alternate between periods of intense output and periods during which I just read and immerse myself in ideas, language. Because of my full-time job, I don’t get that many hours of uninterrupted writing time throughout the week. I write down phrases or ideas that come to me in a notebook or on my phone.

When I’m writing consistently, the process is usually painful and slow. And so is the revision process. Sometimes a poem is a gift in that arrives fully formed. But those are rare.

Randal Eldon Greene: What advice do you have for young people who are learning to write poems about their lives and the lives of others?

Rosanna Young Oh: As a poet, I’m not in a position to give advice—my journey has just begun. Honestly, I’m figuring things out as I go.

Purchase The Corrected Version.

© 2023

About the interviewer:

Randal Eldon Greene is the author of Descriptions of Heaven, a novella about a linguist, a lake monster, and the looming shadow of death.

His Instagram is @RandalEldon Greene

His website is AuthorGreene.com

You can also support our work by buying cool merch like mugs and t-shirts.