Interview with Julian Mithra - 2023

Interview #19 (Short Fiction, Poetry, Experimental Novel, Hybrid Novel, Experimental Fiction, Historical Fiction)

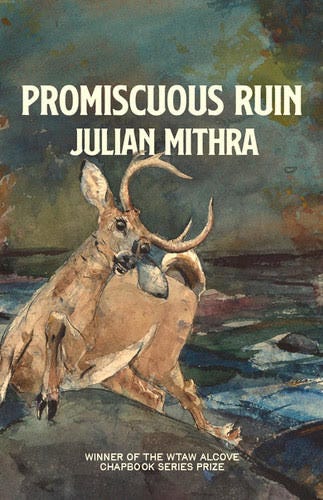

Julian Mithra hovers between genders and genres, border-mongering and -mongreling. Winner of the 2023 Alcove Chapbook Prize, Promiscuous Ruin (WTAW) twists through labyrinthine deer stalks in the imperiled wilderness of inhibited desire. An experimental archive, Unearthingly (KERNPUNKT, 2022) excavates forgotten spaces. Read recent work in Arriving at a Shoreline, warm milk, Punt Volat, The Museum of Americana, and newsinews.

Randal Eldon Greene: Hello, Julian Mithra.

As I've been telling people about your book, they keep ending up asking the same question: So is it fiction? I know that you—or at least your publisher—are calling it an "experimental novel." So I do tell them that, yes, it is, but it's also poetry and lists and word games. Ultimately I feel Unearthingly is a work of thematically-connected fragments with a large dollop of connecting narrative tissue. Would you agree with or refute this assessment? And, I guess more importantly, how have you been describing your book to those around you?

Julian Mithra: I’m heartened that potential readers are contending with the inadequacy of market-created genre descriptions, as I spent so much time with truths as they are rendered by The Archive. Are the ways we approach records of our human experiences determined by disciplinary expectations? Are we distanced and absolved by entertaining ourselves with fiction, whereas we’re haunted and compelled when we’re in a ‘historic’ archive? Or the opposite. We might give ourselves permission to be emotionally entangled with imaginary characters and folkloric landscapes, but coolly analytic in academic research. Ultimately, I’m into acknowledging that power dominates these questions of access to The Archive — both as subjects and as experts. In creating and recreating editorials, poems, lists, and textbook lessons in content and graphic design, I interfered with the cues we’re accustomed to relying on to determine a text’s authenticity, audience, force, authority, and claim to knowledge.

Just as there are physical resource extractions at play—ore and the land above it—so are there narrative resources, extracted and displayed as part of the great machine of settler colonialism and storytelling. I’m curious about the narrative tissues that you gathered to connect the fragments. I like to imagine that the fragments are connected through the process of archiving itself. The main present-time plot is Cheeky’s record- keeping. She’s creating her own diaristic account of the underground. She’s an archivist.

My writing friend L and I have been talking about this genre question related to memoir and decided that it’s often a legal issue. Akhtar’s memoir Homeland Elegies is published as a fiction to protect against libel. Hopefully, we’re collectively realizing how inadequately these media categories hold art. More and more, journals are including a “hybrid” category to cover visual poetry, multimedia work, collaborations, nonsense, sketches, etc. Hybridize hybridize hybridize.

My project needed to rub right against extant records, render them in a recognizable form, gesture to shared reality, and yet activate epistemologies that aren’t academic, aren’t analytic. From the writer’s perspective, we imagine that certain ways of imagining open when we let go of genre boundaries. Personally, I couldn’t write this book when I told myself I’m writing a novel. It was only once I said I would create texts that these forms coalesced.

Like many things, I’m interested in the dissolving of binaries, of boundaries. So questioning and prompting others to question, what do I know about the history of the Western States? Where did I learn it? How am I relying on human-made inquiries to account for non-human objects? Where do suppressed histories go? Who’s been silenced?

When I describe this book, I call it an experimental archive — an experiment in archival processes of language, an offering of an archive for the reader’s experimentation in knitting their own connective tissues. In one instantiation, I aspired to create an edition of loose leaf pages: clipped newsprint, ripped out magazines, pamphlets, brochures, maps, handwritten field notes, and a leatherbound journal as The Underground Atlas, in a box, and let the reader assemble and order them as they liked. The reader as meaning-maker.

Randal Eldon Greene: It's rare that I've come across a writer who is as concerned with the medium as the message, despite that old cliché of the medium being the message. Yet there are works which sometimes point reflectively back to their own form. What does it mean that I bought a pamphlet that came with a match in order to give me the option of burning it when done reading? Acknowledging that The Archive is destructible, damageable by willingly offering the tools of erasure, or at least crozzled transformation, seems to be the point. It's a point not dissimilar to The Underground Atlas. And it's also not dissimilar to what you're doing with Unearthingly, though much less (if you'll pardon the poor pun) inflammatory in its methodology.

With Unearthingly you've taken a multitude of written forms and transformations (terraformations?) of form to explore the idea of form itself and authority over those forms. For me, your book hangs together primarily not through narrative (though there seems to be a couple of stories being told), but through the theme of minerals and mineral extraction through mining. Mines, mining, and the precious metals of the earth here are very real things, yet they're working thematically to get at the heart of your conceptions. Tell us a little about how you sought to use these ideas to explore your critique of the way we create and keep accounts of history and story (The Archive). I'm also curious what the process of researching mines and mineral extraction looked like for this project.

Julian Mithra: Thank you for this attention to resource extraction as a technology wrought upon the land and treasure-hunting as an extended metaphor.

Historically, the 30s were a period of industrializing mining, so individual miners (sort of independent contractors) no longer controlled their labor. The expertise of miners, their informal ways of apprenticing and mastering these skills, were being eroded by corporate structures, machines, and formal modes of teaching, like the Colorado School of Mines. This is an old story: local, creative, integrated labor is abstracted and cog-ified. In parallel, the ways that mining was represented in guidebooks was romanticized (related to the invention of the Western as a popular genre that glorified the heyday of frontier lawlessness). As soon as we have corporations making a claim for modernity and progress, we need a tradition or an obsolete method to deride as old-fashioned. These “terraformations” (<3 that word) reflect ideologies of land itself as well as labor.

Off and on for five years, I researched historic media related to mining, from period college textbooks to nostalgic Lost Mines of Colorado/New Mexico/Arizona books that mythologized hidden treasures to 19th century guidebooks for amateurs hoping to strike the motherlode to U.S. Geological Survey reports on minerals. I watched YouTube videos of amateurs exploring abandoned ore and coal mines. I read a couple of standard disciplinary approaches to the labor movement, like What's a Coal Miner to Do: The Mechanization of Coal Mining (which included a lot of interviews with miners in the 20s). This material ended up being informative here and there when I needed to know the details of smelting, but primarily it was to absorb the language that, as you so aptly put it, constructed “form itself and authority over those forms.” How is it intimidating to hold a heavy textbook with tiny print and footnotes? How does that contrast with flipping through a pulpy magazine with an ad for a rock tumbler and a suspenseful adventure in penetrating an Egyptian tomb? These expectations for information or entertainment emerge from graphic design. In common, though, capitalist American optimism oozes through. If a miner is abjectly thumbing a greasy report of the latest claims, there’s the expectation that he could succeed, just as Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats bridged suffering and imminent relief. I aspired to capture the range of idiolects in these forms and also their common thread—the intensification of progress during the Depression incumbent upon environmental devastation and racist policies.

Aesthetically, I can’t deny that copper, silver, and gold romance me. They’re shiny, dense, gorgeous, timeless. They’re all surface. Gold is unchanged for millions if not billions of years. These metals are elemental, unalloyed, pure. Though the politics of their usefulness have evolved, their materiality hasn’t. Cheeky longs to contact her own precious, inalterable essence directly (sensorily?) rather than through language or through thinking. That meant rendering ore as sensually and kleptomaniacally as possible, whether through comparing it to a bride, as in “A Field Guide to Prospectating” or in exaggerating the passion it evinces, like training badgers to dig for ore in the glossary entry for fossorial.

In parallel, I identify with that unquenchable almost-ness—that if only we could get a bit more information, go a bit deeper, work harder, and develop a scad more self-reflection we’d arrive at the land of milk and honey. The process of excavation emerged as a metaphor for processing trauma individually and collectively, mining for that core beauty. The deeper Cheeky goes, the less she can rely on dominant narratives of quest→reward, the more she is compelled to go inward. I like to imagine she reaches the limits of beginning-middle-end storytelling (as she reaches the limit of the tunnel) and needs to keep going.

Randal Eldon Greene: Cheeky is a character in the town of Goldened—a town intimately connected with the mining industry. Despite being from an immigrant family, Cheeky is in some ways more connected to and knowledgeable about Goldened than her peers. We see Cheeky as she deals with the repercussions of this dual background. In fact, much within the pages of Unearthingly are related to Cheeky, whether it be other references to her hometown (e.g., the "Goldened Gazette" sections), passages lifted from an adventure tale she is reading, glimpses of Cheeky's life at school, and sections of the Underground Atlas within this book which she is ostensibly writing.

Was the character of Cheeky there from the beginning, when you first started researching and collecting material for Unearthingly? In some ways, it feels like she wasn't meant to be this central pivot point of the book, possibly because whole sections are unrelated to her life. Yet, she works so well as this pivot point that I wonder if I'm mistaken and maybe she was the original center you intended for Unearthingly.

Julian Mithra: A pivot. I like that mechanical word. Like the knuckle of a hinge through which the other texts must pass. Cheeky began her relationship to Goldened as a student in the 70s nostalgic for the good-ol-days. Originally, she researched the mythology around the town’s founders, infrastructure projects from the WPA, and industry. She was sneaking into the back storage at the library downtown and stealing reports. Eveline Lovelace, a shut-in editorialist at the gazette, needed Cheeky to attend events and report on his political enemies. Cheeky befriended a genderqueer drama director, Vivian, who was restoring the theater to its heyday during the New Deal’s Federal Theater Project.

In this mystery version, all the texts appeared diagetically. So, if Cheeky was delivering an editorial, she opened the manila envelope. If she was recording her observations on an abandoned aqueduct, we read her notes. I was into the old typewriters and theater queers aesthetics. (In one scene, Vivian found the stowaway locked in a costume trunk. Climbing out, she announced, “Hey, I’m Cheeky,” and Vivian got to say, “Aren’t you just!”) Ultimately, this felt more and more like a project that a different writer would pull off, like Virginia Hamilton or Linda Sue Park, but I was motivated by a “should” voice in my subconscious. It’s funny to me now, of course, that I have distance from all those outlines and character sheets.

Two events precipitated my decision to trash genre expectations and write into my folklore roots. The first: reading Djuna Barnes’ Ryder in the summer of 2019. I adored it from the first page—saucy, histrionic, and seemingly in an invented Victorianese, so playing with “nostalgia” for eras before high modernism. But I couldn’t stop giggling when I got to a poem about a guy’s obsessive love for a cow in a fake Yeats-like rhyming couplets idiom. It goes on for nineteen pages—far past the point at which you would get the joke and into a hypnotic, unnecessary audacity. Why sustain the ridiculous? This poem gave me permission to let go of readability and move toward audacious playfulness.

The second: I received a scholarship to attend a workshop on “hybrid” writing forms with Lidia Yuknavitch. During our first circle, Lidia asked each person how they came to non-normative structure. It was like one of those math genius movies with scribbled equations and graphs constellating my head; a half hour concentrated lecture on hybridity. From neurodivergence to experiences with literal voice (implicating capital-V Voice) to gender inbetweenness, to critiques of narrative popularized by settler colonialism, to multilingualism. I had that rare moment of belonging. The next day, I wrote one page using a “stratigraphic” structure with scenes that dug through the layers of story and hit bedrock. (That stratigraphy appears, almost unchanged, as the “Appendix.”)

More and more, I shuttled Cheeky’s plot points and replaced them with ridiculous language and diagrams and talking animals. So some connections were lost, like how the folk tale about the arrogant boy Carlos and the drought is a bedtime story that Cheeky tells to her cousin-brother Silas because she resents his boyhood. Without appearing as a doing character, Cheeky’s curiosity and disdain cast the surrounding texts in a certain light.

Randal Eldon Greene: Offsetting readability in favor of playfulness (of form, of language, of the idea of story itself) is the kind of advice you'll never get from professional fiction-writing coaches. But I argue that it is exactly the kind of thing you'll learn from the best movers and shakers in storytelling.

I do have a caveat with that though. If the playfulness uses personal symbolism and gives the reader no entrance into that system of symbols and meaning, it makes readability entirely inaccessible . . . well, maybe accessible only with the aid of a hypothetical outside resource (author's diaries, interviews, etc.). While such writing has the potential to be interesting nonetheless, it does not invite the reader to play because such writing doesn't share the rules of the game.

Unearthingly is a difficult book, but I think it allows the reader to dig into it and to mine meaning based on what the text itself gives us (and, yes, I'm again punning here). In writing such a difficult book, how did you manage your desire for playfulness and a need to make that playfulness accessible to any reader who wants to dig a little (or a lot) for it?

Julian Mithra: At first, I had not cultivated enough faith in playfulness, intertextuality, and a rich symbolic landscape. I assumed that revising was necessarily a destructive process, influenced no doubt by “kill your darlings”-ish colonial impulses within workshop culture. I even splurged on a normal six week prose class with a nose-to-the-grindstone mentality. In discussions, my material elicited an unexpected amount of ire and frustration. I still remember when the facilitator advised me to give Cheeky a “love interest” so the reader can better connect to her queerness. Yikes. Venting to a good friend, he reframed their response as an indication of power and reminded me that being disruptive is uncomfortable. With that support, I was able to reclaim some of that power and drill down on each of the frictions that had elicited such emotional reactions, from “inaccessible” mining jargon and obsolete language, to Cheeky’s queerness as an affinity with non-human subjects, to the illogical geography of her journey underground.

Later, when I’d dismantled and remantled everything as an imaginary archive, and healed that rupture between my inner critic and my creative self, I could return to the question of accessibility from an authentic place of curiosity. To that end, I consulted with EJ Colen through Black Lawrence Press in the “hybrid” manuscript category, optimistic that a genre-bending writer and instructor would have sensitivity to balancing expectations for story with experimentalism.

Indeed, Colen offered invaluable feedback in a voice I could listen to. Specifically, I only included one or two glossary entries, and they noticed that this voice from the rational, familiar form of a definition and etymology could help give a reader validation in deciphering themes. I also remember they highlighted the anaphoric, “A man dug a hole. A man chopped a tree. A man lit a torch and looked around,” as a moment of concentrated story that resonated with the whole. These noticings invited me to add more glossary entries and be mindful of other mini-arcs.

Another move was to create the interstitial scenes, both to mark the different sections, and as miniature language-mines. I’d search for a long word, say acknowledgment, and try to “mine” the word by stripping away letters. So acknowledgment → knowledge → ledge or know or knoll (being punny) → now or owl or led. Many long words couldn’t be mined and many of the series didn’t lend themselves to a vignette. I think these ended up tracing simple progressions through toxic masculinity (like the bully William messing with a snake) or small town patriotism (the county fair) or the museumification of culture (the grizzly bear).

Contemporaneous pulpy magazines, like Adventure and Amazing Stories offered an extreme model for entertainment over poetry. To my modern sensibility, they were hilariously melodramatic and ridiculously adverbial. That influenced some of the descriptions of tunnels as well as the suspicious characters with The Owl and their slang-laden dialogue. I wanted to infuse Cheeky’s sections with some of that anticipation and spookiness even though it would be interspersed with other surreal or non-pulpy intrusions.

Randal Eldon Greene: There is a theme of claiming or reclaiming power through Cheeky's unearthing of history, exploration of geography, as well as through your language-mines and the symbolism of mythos. What I'm unsure of is if reclamation is Cheeky's ultimate goal. What is Cheeky truly after? And how does the text as a whole differ in its ultimate goal, even while using Cheeky to achieve that goal?

Julian Mithra: One of Cheeky’s first intentional actions is defacing a textbook in order to re-inscribe it with her own writing. And her snarky essay about Goldened being named after an undeserving founder demonstrates her resistance to celebratory history. But I believe that Cheeky is motivated by self-protection. The underground spaces safely contain her grief. These wombs de-emphasize sight as the primary mode of understanding and allow her to sink into touch and smell. Her body is experienced through embodiment, rather than as a representation of identity markers. Even language seems to transform into something of a tool for compassion and lateral thinking.

The assemblage of texts or the treatments of texts question epistemology and, relatedly, goals. Or the attempt for language to establish a field of knowledge based on authority. Those goals get inverted or disturbed or mocked. So an editorial column, whose goal is to persuade readers to agree with the political opinion of an expert, ends up sounding like a jerk and not winning our sympathy. A guide to idiomatic English for language learners can’t explain or translate a maxim like “look before you leap.” A guide for how to conserve food in a root cellar ends up personifying the vegetables and casting the grower as someone who maliciously tricks them into not reproducing by denying them light.

Is dissolving of texts that rely on disciplinary knowledge like gardening, economics, archeology, and linguistics itself is a goal? I don’t think so. Partly because the dissolving happens from within language itself, rather from asserting an alternative source of expertise. In the entry for “Argus Mine,” Cheeky records an encounter with an untraversable terrain blocked by clay. She advises bringing Argus as a helpful companion, the giant with so many eyes that nothing escapes his noticing. Argus reminds her of a flashlight or lantern that can observe without blinking. The name of the mine offers a clue for how to protect herself via hyper-vigilance. Allying with this spirit soothes her fears.

Another reversal occurs in the folk tale about a beaver lodge. Instead of anthropomorphic characters, the beavers are the landscape and water is the character. An ocean wave waves backwards from the shore, up a river, and into a lake. It’s indifferent to its destruction and prefers being displaced. It’s a literalization of the idiom “against the current,” emphasizing disruptions and dislocations and arriving in pleasure—the wave enjoys the echoes of her patterns on the surface of the lake. Narratively, it’s another unfolding of rebellion.

Randal Eldon Greene: You mentioned Cheeky's queer identity earlier. I'm curious how important it was to you for the character to reveal this side of themselves? It wasn't evident to me while reading the text. But now I'm seeing all sorts of potentials in how you possibly approached this—both consciously and unconsciously.

One potential angle of exploration I’m wondering about comes from the tension between historical fiction’s concern for realism in sexual identities and a looser approach to ahistorical imagination. In a sense, you’re reclaiming the space of adolescent queerness that might not be captured in The Archive.

Julian Mithra: I’m invested in queerness that exceeds the narrow and dated category of sexual orientation. Cheeky’s queer in the sense that her intimate relations aren’t with humans but with books, animals, spirits, and places. I’m reminded of bell hooks’ attention to the intersectionality of blackness, queerness, and womanhood in a presentation, “Are You Still a Slave? Liberating the Black Female Body.”

Queer as not about who you’re having sex with (that can be a dimension of it) but queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.

The ways that Cheeky finds to embrace her “at odds” with everything are inventive and creative. She prefers identifying with heroic masculinity in the pulp horror adventures of the Dixon Brothers. As I spoke about before, she creates her own antithetical histories of her town. She’s mothered by chalcedony and grizzly bears rather than human women.

I also designed Cheeky to be coded as queer for readers who spent their youth decoding fiction. For example, I recently got nostalgic for John Bellair’s pulpy horror series featuring Anthony Monday, a nerdy tween, his best friend, a clumsy librarian in her late 60s, and her brother, a bookish bachelor. Set in the early 50s and intended for a middle school audience, nothing about these stories are canonically gay. But when the librarian’s brother leaves behind FOUR meerschaum pipes, and his sister takes this as evidence that he’s been kidnapped, I know he’s queer. Anthony’s devotion to an elderly woman, who his mother finds too odd for polite company, also signals a queer connection.

Intergenerational nurturing outside of the nuclear unit can signal queer family. Like The Tramp’s parenting in The Kid (Chaplin, 1921) or Addie, with cropped hair and Newsies cap, swindling dupes in Paper Moon (Bogdanovich, 1973) with her maybe-maybe-not pop during the Depression. A few gestures, like Cheeky’s overalls and being bullied by a white boy and feeling resentful about her cousin’s boy privilege, clue in some readers. I prefer to begin from a place of queerness, rather than depending on a text to out itself. At first, that’s born from necessity (being starved for lesbian and genderqueer representation as a young person), and now I cultivate it as a reading technique.

Finally, I thought about what queernesses would have been available to a small town chicanx girl in the 30s. Cheeky doesn’t live in Harlem, Mexico City, or the left bank in Paris. But she can steal her Uncle’s hand-powered flashlight. Her idea of fun is climbing into abandoned mines. She plays with language. There aren’t any material choices she can make to resolve her bullying or resist anti-union violence or deportation, yet her vibrance originates with her willingness to accord subjectivity to non-humans. Her desire for connection extends her potential for intimacy.

Randal Eldon Greene: You know, one of my favorite writers both encoded queerness into her texts and was equally playful and deep—Gertrude Stein. I think the individual parts of Unearthingly are perhaps more accessible than a lot of Stein's writing, but I believe that those who enjoy digging into her often dense prose would also appreciate the depth found within your collection.

Our conversation has helped reveal to me more fully why your book was so enjoyable to read; I often sense or manage to uncover the first layer of depth in a piece of writing like this. It's the underlying structure of high-density literature which brings me pleasure as a reader, even though it necessitates multiple rereadings. In fact, because it necessitates multiple rereadings, I find my pleasure and appreciation increasing with each visit to the text.

Who are some authors that you feel are similar in a high-density way or who you believe an appreciative reader of Unearthingly would also enjoy?

Julian Mithra: Gah, Stein is near and dear to my heart of course. And I completely concur that density itself appeals to me across genre. Certainly, poetry and lyrics build on dense bones, but I’m also for the baroque density of surfaces, too.

Looking over this year’s reading list, one remarkable book springs to mind. I lucked into a reading with Valerie Hsiung and immediately pre-ordered To Love An Artist. It’s a genre-queer journally, essayistic, surreal meditation that I’m still not too conclusive on. I was especially taken by a form innovation—the split paragraph. A paragraph will be moving right along with its predictable syntax and capitals and periods, then it’s

interrupted for one

or two lines, a poemlet

before returning here once again to standard prose. As a reader, these hiccoughs shifted my frame — the straightforward referentiality I’d expect from prose, meaning that Hsiung’s sharing her thoughts about the world we both live in — is interrupted as I consider surrealism, irony, lyricism as other ways to interact with language. One section begins, “If one has set out to say one thing , to say one thing and then you will have said it and to say so you will mean it finally.” (81) I kept catching myself in these loops of truthiness, assertion, persuasion, how writing constitutes self, etc.

The other example of density to which I aspire: The Kingdom of This World by Alejo Carpentier, translated from the Spanish in 1957. In a single paragraph, he might condense an entire racialized class structure. He expertly uses images so unusual and so macabre that they’ll stay with me, such as adding fresh bull’s blood to the mortar of an ominous fort to ensorcel it with strength. The scope of this novel is the vast, tragic history of Haiti a la War and Peace, yet it’s “only” 180 pages.

I appreciate being able to return to beloved novels for second and third readings and find more to absorb. I’m grateful for texts that taught me about my magical Venn diagram between “books about nothing” (low-plot narratives) and “books with dense ideas,” like Jane Bowles. Or even queer theorists like Jack Halberstam and José Muñoz who shrinky-dink enormous questions like the nature of desire into books.

Purchase Unearthingly online.

Purchase Promiscuous Ruin on Amazon.

© 2023

Thanks for reading Hello, Author! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

About the interviewer:

Randal Eldon Greene is the author of Descriptions of Heaven, a novella about a linguist, a lake monster, and the looming shadow of death.

His Instagram is @RandalEldon Greene

His website is AuthorGreene.com

You can also support our work by buying cool merch like mugs and t-shirts.