Interview with Charlie Selkirk - 2023

(Short Story Collection, Bizarro Fiction, Absurdism, Humor Writing)

For no particular reason or purpose Charlie Selkirk was born in the northern town of Hull. Apart from allegedly nearly drowning in a very shallow bath, he had an uneventful childhood. He attended the University of Durham in an attempt to extend his limited educational horizons. The results were sadly disappointing.

Surprisingly in the circumstances, he elected to move to the Midlands with the aim of extending the educational horizons of the young people he found there. The results were similarly disappointing.

To escape his mounting failures, he moved further and further to the West of the country. Inexplicably, he ended up in a bleak location on a hillside overlooking the sea, on the border of Cornwall and Devon, with six goats. As the goats died one by one, he started to realise the finitude of existence. In 2020 he decided to return to the North to live in Scarborough and await death.

Randal Eldon Greene: Hello, Charlie Selkirk

Getting into your book, I quickly realized I was reading Bizarro Fiction. For those who don’t know, Bizarro Fiction is a modern form of absurdist writing, sometimes utilizing body horror and light science fiction motifs or settings (while always making the sci-fi weird with a refusal to create a coherent world building scheme and the body horror more zany than grotesque). Other great titles of the Bizarro genre include Help! A Bear is Eating Me!, The Greatest Fucking Moment in Sports, and It Came From Below the Belt. Your collection, A Bird of Dereliction, is the crème de la crème when it comes to Bizarro.

I’ve been a fan of Bizarro Fiction for a very long time. In fact, my first publication was in the Bizarro magazine Bust Down the Doors and Eat All the Chickens. I’m wondering if you were aware of this rather underground genre and who you’d consider your influences in your writing?

Charlie Selkirk: Hello Randal, many thanks for the surprising and entertaining questions.

I wasn’t aware of this genre of fiction but must admit that it seems to characterise well the writing in A Bird of Dereliction. With my publishing team, for a long time, we had been trying to find the genre that it might fit into. We considered Slipstream and Transgressive Fiction but neither seemed quite right. Bizarro Fiction seems much closer. I certainly wasn’t consciously writing in any genre but it seems to fit well.

The actual influences go back a long time. When I was a teenager I read quite diversely but probably mainly Science Fiction. I was particularly fond of Ray Bradbury. Like a lot of people at the time I would have loved to have been J G Ballard, following his ‘descent’ from writing catastrophic SF to The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash. They fascinated me. I did have a go at writing, and I had a character known simply as ‘the corpse of the terminal drug addict’. Somebody pointed out that this was clearly derivative of Ballard. I realised that he was right and that Ballard had to be vigorously expunged from the process of writing.

I suppose things considerably changed when I had a strange crisis at the time of leaving university.

Unfortunately, I encountered the ‘Sisyphean Catastrophe’.

I’d been a fairly poor student of physics and quickly realised that I wasn’t going to become the next Einstein. As far as physics was concerned things had been going downhill for some time. At the beginning of the second year we were studying the quantum structure of the Hydrogen Atom and we were set a fairly tricky homework problem to determine its energy levels. I hadn’t the faintest clue as to how to do it. But then I had a eureka moment and it all came clear.

Triumphantly I delivered my answers to the tutor and the next week attended the tutorial to receive feedback on my excellent work. It turned out that I had got the whole bloody thing wrong. I couldn’t believe that the universe had failed to function in the manner that I thought fit. I was furious.

That evening, moodily, I went to the college library and by chance discovered in hardback a trilogy by Mervyn Peake. What struck me about it was that the cover illustration had been drawn by Mervyn Peake. He was an artist as well as a writer. It was a simple rendering of a pillar of crumbling masonry on a white background in pen and ink.

I realised that it was the sort of thing that I could have done. I was kind of hooked. No more physics tutorials for me (don’t blame me, blame the universe). I really liked the idea of writing something and illustrating it but of course it couldn’t prove as simple as that.

The book followed the adventures of Titus Groan, the Lord of the decaying Gormenghast Castle as he performs endless meaningless rituals whose purpose had long been forgotten. It was good as far as it went, but then it didn’t manage to get very far. It didn’t deliver its promise. It was long and rambling and didn’t really have anywhere to go in the end.

I had already encountered Peake a few months earlier in the summer at the end of my first year at university. I actually failed my first year exams because I’d neglected to complete and submit a computer project and, without it, I couldn’t possibly pass the course and carry on. My physics tutor cheerfully told me that all I had to do was finish the project during the summer recess, resit the exam and then I could carry on my illustrious journey in the world of physics (it didn’t help that I didn’t have the faintest idea as to how to program a computer).

Through the summer holidays I was supposed to submit programs with the aim of completing the project. It was while on holiday in Torquay that I first became acquainted with Mervyn Peake. I came across a book called The Inner Landscape which contained novellas by J.G.Ballard, Brian Aldiss, and Mervyn Peake.

This first encounter with Mervyn Peake was more inspiring than the second.

The novella by Peake was called Boy in Darkness which was radically different from The Gormenghast novels. Although not referred to by name, it involved the same character of Titus. Oppressed by the endless rituals in the castle, he escapes on an unpiloted boat on a river that draws him magically to a sinister realm. There he meets a goat and a hyena that are incredibly threatening to him. I certainly didn’t think that he was safe with them.

The Gormenghast novels, although they feature an astonishing castle the size of a city and bizarre characters, do not contain magic like in Grimm’s fairy tales, but Boy in Darkness is quite different. It turns out the sinister realm Titus is drawn to is ruled by a blind, white lamb.

Despite being strong and threatening, the goat and hyena both fear the blind, white lamb which appears to be defenceless. They hear the bleating tones of the lamb summoning them to his castle. The goat and the hyena seem anxious to take Titus to the lamb as an offering. It seems that it was through the art of the blind white lamb that the goat and the hyena had been fashioned from human creatures and the intention of the lamb was to do the same with Titus.

When Titus is confronted by the lamb, he manages to grab a sword and slashes at the white lamb. But it turns out that the lamb has no substance. There is nothing but wool flying about. This has the effect of freeing the goat and the hyena. They appear to have become human again but one with the strong appearance of a goat and the other a hyena. Grateful to Titus, they return him to the boat on the river which draws him back home where search parties are out looking for him.

What struck me about the story was that it was a simple allegory of evil. There was nothing real about the lamb. All its threatening, controlling aspects were due to suggestion. There was nothing really there. The story made a huge impression on me and I certainly wanted to read more of Mervyn Peake. But there was nothing that matched the simple elegance of Boy in Darkness.

By the end of the summer, unsurprisingly, I’d failed to complete the computer project and faced expulsion from the university. Only one option was available to me.

I was forced to cheat.

I borrowed the project of a fellow student and submitted it as if it was my own. Who said crime doesn’t pay? So I have to confess my degree in physics is a deceit.

As time went on I became more preoccupied with the overall meaninglessness of human existence and, after completing my degree, went on to do ABSOLUTELY NOTHING.

I certainly saw life in Sisyphean terms, referring to the bloke in the Greek myths who is condemned by the gods to push a huge boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down the other side for eternity.

I must have been a nightmare for my mother.

‘So……Why did you have me?’

‘What is the point of going out to work in order to sustain yourself so that you can go out to work the following day?” etc, etc.

I didn’t realise at the time that there was quite a bulk of literature sympathetic to my Sisyphean perspective. My general viewpoint on human existence probably did damage my life. I certainly didn’t go forth and multiply.

To escape the morass, I (slightly unhappily) enrolled on a postgraduate teacher training course in Leicester. Due to my general apathy, I hadn’t bothered to organise any accommodation and for several weeks after turning up in Leicester I was semi-homeless. I met up with another student teacher in the same predicament called Mark Gotem and we joined forces to help cope with the relentless demands of the Sisyphean Catastrophe.

Mark had done something I’ve always considered to be quite brilliant. When he was a French Language undergraduate, he was required to write a dissertation on a French writer. Controversially, he chose the Irish writer, Samuel Beckett. Beckett originally wrote in Irish but when he moved to France thereafter wrote in French. Mark’s strange choice had to be approved by the examination board of the university. And so it was Mark who introduced me to Samuel Beckett.

As we endured our quasi-homelessness and faced the horrors of actually entering classrooms as ill-formed teachers, we decided to set the theme for the term—namely, ‘The meaninglessness of human existence’. I found it oddly stimulating and it seemed entirely appropriate when we finally found rat-infested accommodation in the red-light district of Leicester. Despite the unfolding catastrophe around us, we still found time to amuse ourselves.

I remember going to the theatre to watch Endgame by Sam Beckett. More Pricks Than Kicks and other works by Beckett appeared on the bookshelf in my dank, dingy room.

I think, in a difficult way, that Samuel Beckett was quite a strong influence (I don’t find his writing exactly easy and to this day; I’m still struggling to make sense of the Beckett trilogy and the shorter prose work). But the influences of the time were broader than that. I also became aware of the Theatre of the Absurd and I was particularly taken with Alfred Jarry and The Ubu Plays. The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race I thought was exemplary.

Jarry apparently lived in what was effectively a cupboard between floors in a block of apartments. The room I occupied in our rat-infested accommodation didn’t have a proper window. It was made from that frosted glass that was reinforced by a grid of metal wires and admitted only fractured light. It was the sort of window that is used for security in warehouses, etc. I felt a degree of complicity with Jarry. But the poverty and misery that Jarry died in seemed extreme and unnecessary.

I gradually took stock of The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus which certainly accorded with my viewpoint along with its novelisation, The Outsider. I wasn’t that wild about Meursault, Camus’ absurd hero. He seemed to be a somewhat reduced human being. In many ways I preferred A Happy Death with a black and white photo of Camus on the front cover smoking a rollie. He looked very much the cool existentialist; I certainly couldn’t have looked that good. But by this time, surprisingly, I’d gained employment as teacher.

I remember a beautiful sunny day on which I had my 11 to 12 year science class performing field studies on the rough land bordering the school playing field. With my students vanished in the hinterland, I stretched out on the grass in the pleasant sunshine and resumed reading A Happy Death. After a while, a gaggle of giggling schoolgirls joined me. Without asking, one of them took the book off me in order to pour scorn and ridicule on my choice of reading matter (note the fear and respect that I had instilled into them).

‘How on earth can a death be happy?’

Maybe she had a point.

It was in this period I came across an anthology called The Existential Imagination. By this time, I’d left my squalid accommodation in the redlight district and had moved out of town to live in a haunted manor house which was astonishingly cheap to rent. The anthology contained a story by Kafka called, “The Bucket Rider.” It involves a man who has no coal to heat his house in the bitter winter. He sets off to the coal-dealer to beg for a little coal. Because his coal bucket is so light he finds that he is able to climb into it and fly through the frozen streets. He arrives at the conspicuously well-heated house of the coal dealer. The coal dealer’s wife answers the door but claims to her husband that she is unable to see or hear anybody. At the same time, she pitilessly wafts the bucket rider away and he is sent careering with his coal bucket to the Ice Mountains where he is lost forever.

I loved the story because of its simplicity and surreal logic. Due to the narrator’s deprivation of coal, it makes sense that his coal bucket is so light that it enables him to fly through the streets. To me it creates a really funny, evocative image but at the same time it occurs in a situation that is tragic. I wish that I could have written something that good.

Somewhat later, I read Mist [sometimes translated as Fog] by the Spanish existentialist Miguel de Unamuno. It had the usual preoccupations of the existentialists but I don’t remember there being a lot of laughs in Sartre, Camus, or Dostoevsky. But that was not the case in Mist. The novel follows the inauthentic existence of Augusto Perez in his unsuccessful pursuit of love. He is unhappy with the story provided him by Unamuno and goes round to Unamuno’s house to remonstrate with him.

Unamuno finds Augusto irritating and tells Augusto that he has decided to kill him off in the novel. Augusto is really upset by this development but, true to his word, Unamuno does him in. At the very end, Augusto’s dog, Orfeo, delivers a moving eulogy to his deceased master and then he immediately falls dead.

Unamuno manages to convey his existential insights without losing sight of their humorous implications, which seems an essential part of writing to me.

Obviously Kurt Vonnegut was impressed as well. He uses the idea of a character in a novel meeting with the author in Breakfast of Champions.

I suppose it might seem surprising that Kurt Vonnegut didn’t become an influence on me. But I suppose that was because I started reading him too early on. I read Cat’s Cradle when I was at university and found it tedious and difficult to read. In those days I was looking for ‘proper science fiction’ with rockets and aliens that I could relate to and I failed to appreciate Kurt Vonnegut’s cynical take on life, probably not so very different from my own. I wasn’t ready for it. I read Cat’s Cradle (twice) fairly recently and really enjoyed it.

The Sirens of Titan suffered a similar fate. Despite a positive encounter with the story in a jaunty song by Al Stewart, I failed to get more than a few pages into the actual novel.

There are many novels that should have been an influence on me but arrived in my awareness too late.

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov I thought was brilliant. I was about to be investigated for bowel cancer and was assuming that death was just round the corner (needless to say it wasn’t). Reading The Master and Margarita seemed a good way to while away my last days.

I also read The Heart of a Dog in which a surgeon grafts a pair of testicles from a deceased criminal onto a dog along with the pituitary gland into the creature’s head. This really is my sort of thing—maybe I don’t go too much for subtle. The dog transforms into a human being, or more precisely a proletariat. As simple as that.

But one book I’ve reread over the decades which certainly was an influence is Candide by Voltaire.

I was staying with my uncle and aunt on their smallholding in North Wales. Fred, being a literary man, decided that I should read Candide. I didn’t entirely agree. I was reading The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse and felt that that was a weighty enough tome for anybody and was definitely sufficient to occupy me.

But when I got back home I bought a copy of Candide and found that I was captivated.

I returned again and again to the passage in which James the Anabaptist drowns in Lisbon Harbour having been thrown in by an ungrateful sailor. Candide attempts to rescue his benefactor but is prevented by Dr Pangloss who argues that “the roadstead of Lisbon had been made on purpose for the anabaptist to be drowned there.”

Going back a long way is Crow by Ted Hughes. I came across Crow, somewhat incongruously, in the song “My Little Town” by Paul Simon, a perhaps odd introduction to The Life and Songs of the Crow

Randal Eldon Greene: While the level of zany is set on high, your characters take the oddities around them seriously and are, for the most part, quite serious themselves—almost somber. How intentional is this pairing of chaotic environment and character outlook?

Charlie Selkirk: This pairing is totally intentional. But isn’t that how life is? We’re trapped in a sequence of preposterous situations which we almost invariably take seriously. I always aspired to be the cool ironist indifferent to the relentless absurdities, or at least keeping them in perspective, but I’ve failed miserably (so far).

Randal Eldon Greene: I quite enjoyed how you peppered your stories with little ironies for the reader. My favorite was from the story “The Proof of Miracles” in which there’s a father who seems to always be conveniently absent. The young son, Bartholomew, confronts his mother about this. In one of my favorite lines, the mother answers, “It seems to me that Daddy, by definition, occupies a space permanently separated from the space I occupy.” Bartholomew, frustrated with her evasions, eventually lashes out with these words, “Does your notion of Daddy contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Then commit him to the flames, Mummy, commit him to the flames, for he is nothing but sophistry and illusion.”

The irony comes from the fact that the narrator, Bartholomew’s best friend, is revealed to be an imaginary friend himself. While all of them are fun, these stories deserve to be read closely, as they are all full of ironies and symmetries. You must spend some considerable amount of time crafting stories both entertaining but fine-tuned as works of art.

Charlie Selkirk: If I wasn’t peppering the stories with ‘little ironies’ I’m not sure what else I’d be doing.

I hate to say that the line you liked about Bartholomew metaphorically committing his father to the flames was pilfered (ironically?) from Enquiries Concerning Human Understanding by the philosopher David Hume.

Hume, commenting on metaphysical claims, asks, “Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”

Hume was a good writer and delivered some good lines.

Personally, I learned to read using the Dick and Dora [Happy Venture Reader] series. I presume that Bartholomew acquired his reading skills from reading Hume’s Enquiries. But he does come unstuck. Using Hume’s reasoning he concludes that the stern moralising figure of his father is nothing more than fiction created by his mother to spoil Bartholomew’s empirical investigations. But at the end, when it’s all gone horribly wrong, it turns out that the father wasn’t a fiction and he has turned up, presumably to deliver moral retribution.

But all this makes it sound very cerebral which really isn’t the case.

Many of the ‘ironies’ arose from incidents that came from my childhood. For example, the absentee father came from encounters with a rather sad, withdrawn girl called Gabrielle who lived in the street behind ours. She didn’t really join in with us kids in the alley (or the ‘tenfoot’ as it was colloquially known). But I remember pleasant afternoons playing Indians with her (it’s all she would play) in her back garden. It became obvious that hers was a one-parent family. Her mother was very glamorous and rode a bicycle. She was very sociable and always showed great interest in us kids. But Gabrielle was always separate and went to a different school. In those long-ago days, being a one-parent family was quite a stigma. Apparently Gabrielle told somebody that she did have a father but that he went out very early in the morning and returned very late at night which is why he was never seen. It always stuck in my memory.

Similarly, Bartholomew was based on a small boy called Neville who lived opposite. When we were in preschool, I was always fascinated by Neville who was quite uninhibited. He was the opposite of me. He was happy to spontaneously wander about the neighbour’s gardens which I thought was improper and would never have had the nerve to do. I used to follow him about rather timidly. But I could never have done it on my own. The incident where Bartholomew calls Mrs Pugh, ‘Mrs Poo’ was verbatim. He was defiantly a rude boy whereas I was squeaky clean and boring. I felt definitely less substantial than Neville which I suppose might be something to do with the origin of the imaginary friend aspect.

Randal Eldon Greene: There’s a fair bit of social commentary in here, whether it’s on police corruption (“The Nettle Eaters”), the idiocy of government red tape (“Odeur de Sainteté”), or how we as a society approach grief and loss in others (“The Vendor”). Do you start with the absurd—the hole in the ground that begins to swallow a family one by one—or do you start with the theme: the desire to survive in a seemingly nihilistic universe?

Charlie Selkirk: The stories always originate from spontaneously (accidentally?) envisaging an absurd predicament and I just let it develop from there. They usually develop their own momentum.

I think the hole in the ground came from watching an adaptation of a Jane Austen novel during which a coal falls from the fire and burns a hole in the carpet. I simply imagined a similar situation in which matters got out of hand. I don’t think any of this occurs in the Jane Austin story.

“Eva von Crumhorn’s Crumhorn,” followed from a bizarre dream in which I encountered a crumhorn made of glass which was used to serve herbal tea. Then it occurred to me that the herb tea may have been poisoned in order to put an end to someone’s life and so on.

The stories definitely begin with an oddity.

But to me, the theme: ‘the desire to survive in a seemingly nihilistic universe’ seems to be the wrong way of putting it. I’m not sure that people get as far as having a desire to survive in a seeming nihilistic universe. We just seem to get on with it regardless (is there a choice?). There just seems to be a blind instinct to survive whatever the situation. We’re also closely implicated in the perpetuation of the nihilistic universe.

Randal Eldon Greene: I noticed a motif of fire and people being immolated. Was this intentional? If not, what do you think it means that you keep lighting your characters on fire?

Charlie Selkirk: Yes, that is rather worrying, isn’t it? I must admit I hadn’t actually noticed that but I agree that it does happen quite often in the stories. In the (almost completed) forthcoming novel, The Permafrost Kids, it occurs frequently again. The immolations do imply a certain sense of finality.

I always thought it was odd in “Anomie” that the narrator having accidently set his doctor on fire, then walked away with the entirety of the practice on fire apparently without experiencing remorse. Instead, he realises a new sense of freedom previously unavailable to him.

Maybe I have an unfortunate anarchic streak in me, for which I fully apologise.

Randal Eldon Greene: Were the stories in A Bird of Dereliction written over a long period of time or all actually written within a short duration of time?

Charlie Selkirk: Often both.

The next collection of short stories, The Paternal Peristalsis, contains a story called “Necrosis” which I started writing in 1999. It involved some degree of actual work, i.e. looking things up and following references which I found a bit disconcerting and a huge drag. Maybe this is why I prefer doing everything though the imagination as it flows more naturally.

Randal Eldon Greene: What has your writing process been like?

Charlie Selkirk: Story ideas come to me in dreams and on walks along beaches and often are sparked spontaneously in everyday life by the absurdity of the human condition.

I find mornings more conducive. By the end of the day I find myself too bogged down by domesticity.

Writing has sadly been sporadic. More like a drip, drip, drip rather than a torrent, unfortunately.

Sometimes a struggle, sometimes a joy and coming easily in spurts. I wish though that it came faster and more.

I think through my fingers on the keyboard. Some stories are still just on my old electric typewriter.

I have carried several stories in my head for decades, for example, “Mrs Vlad The Impaler”, a nonagenarian vampire.

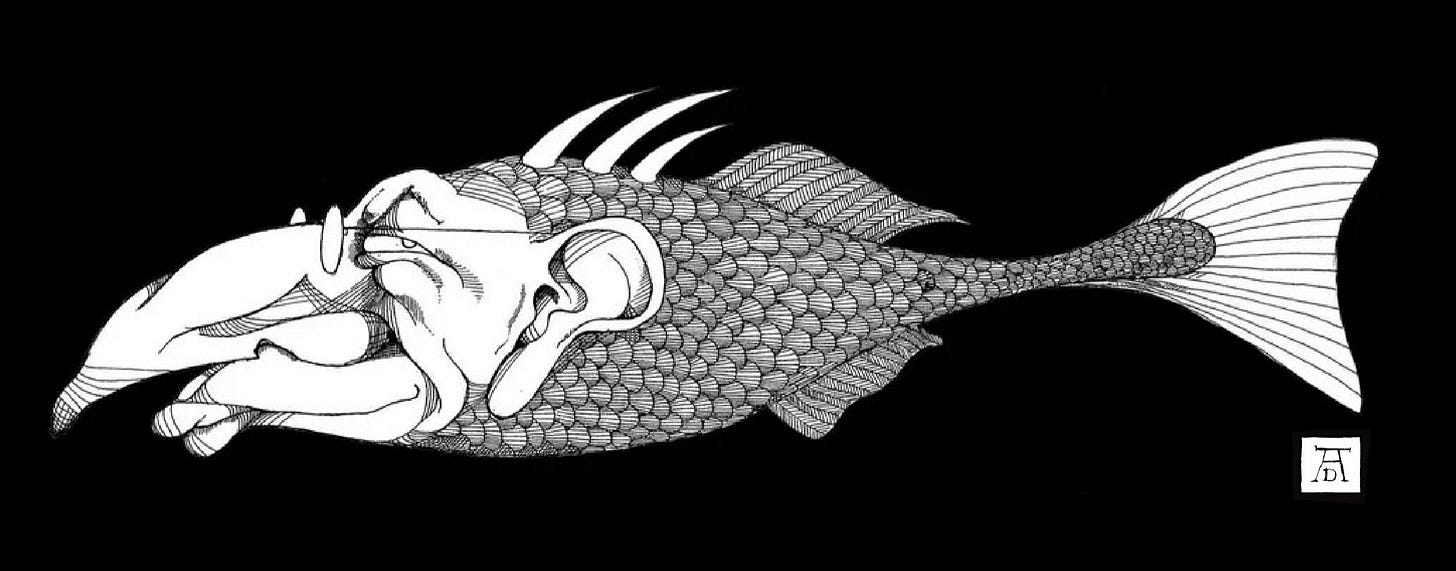

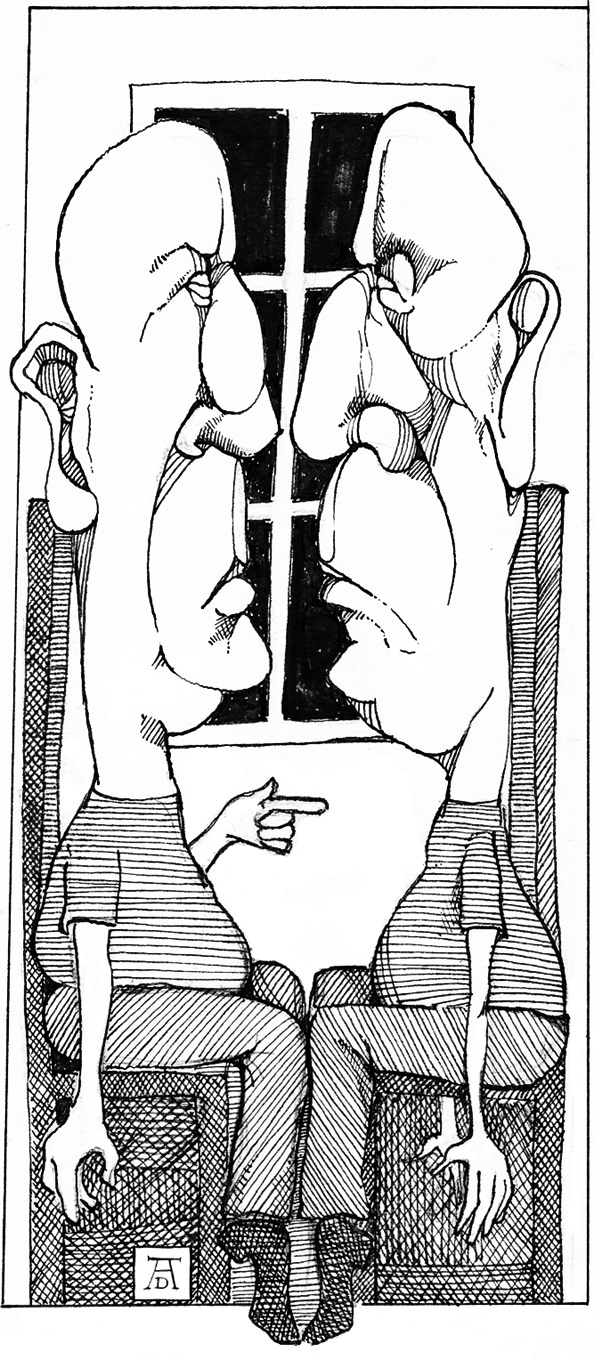

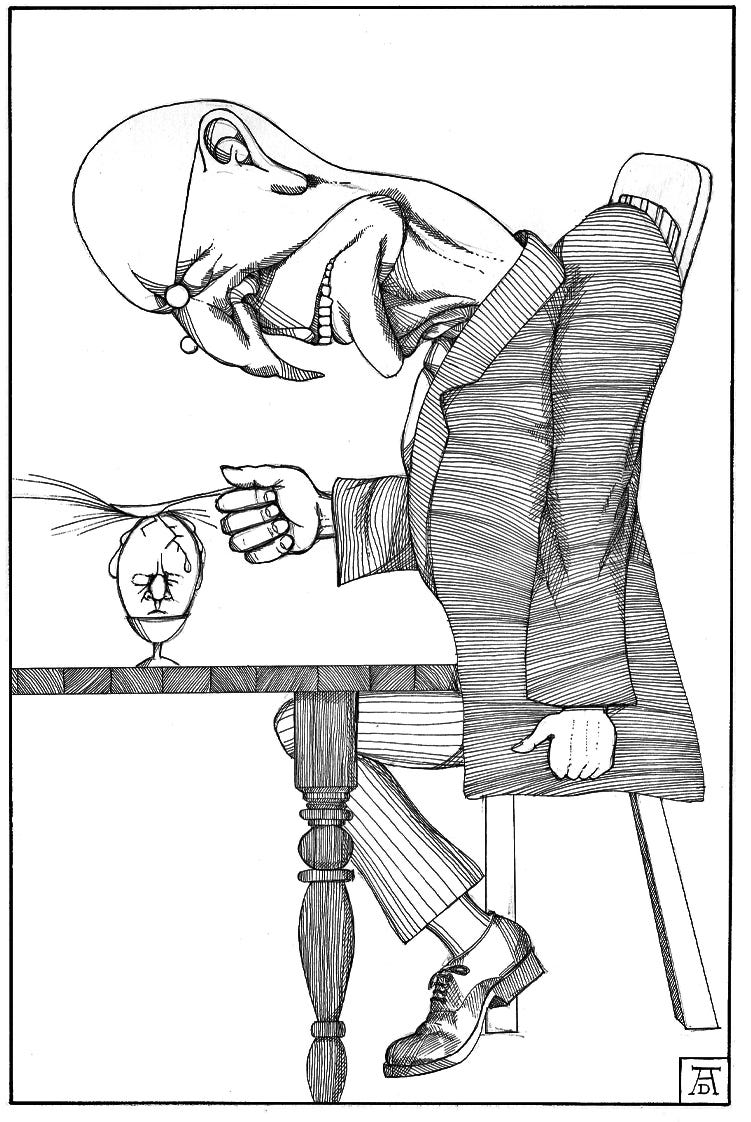

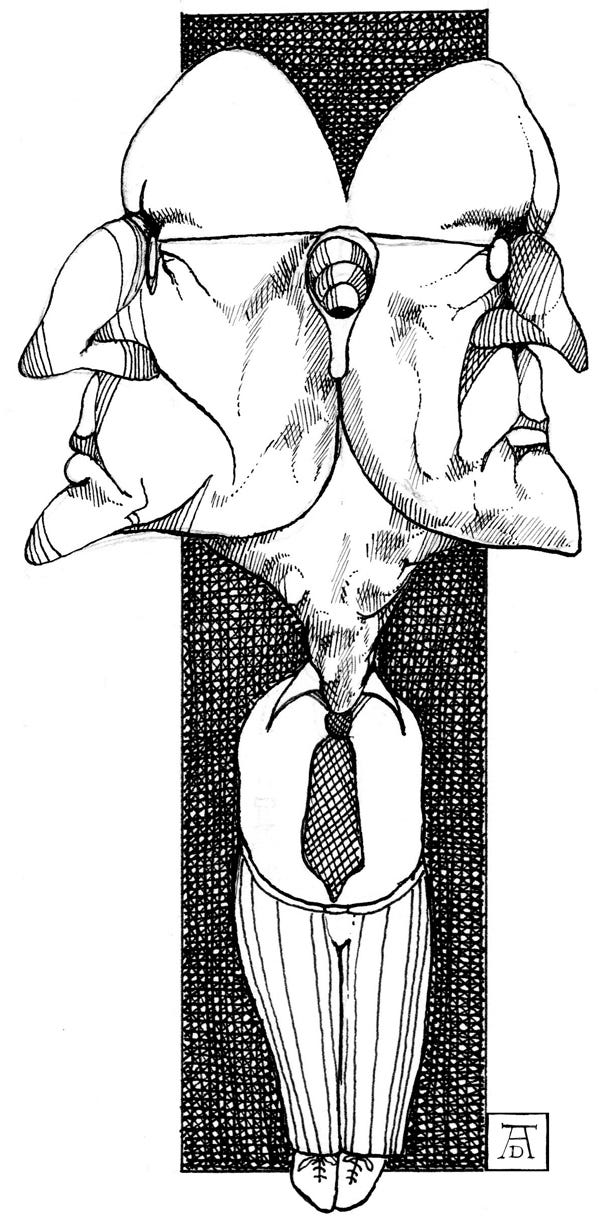

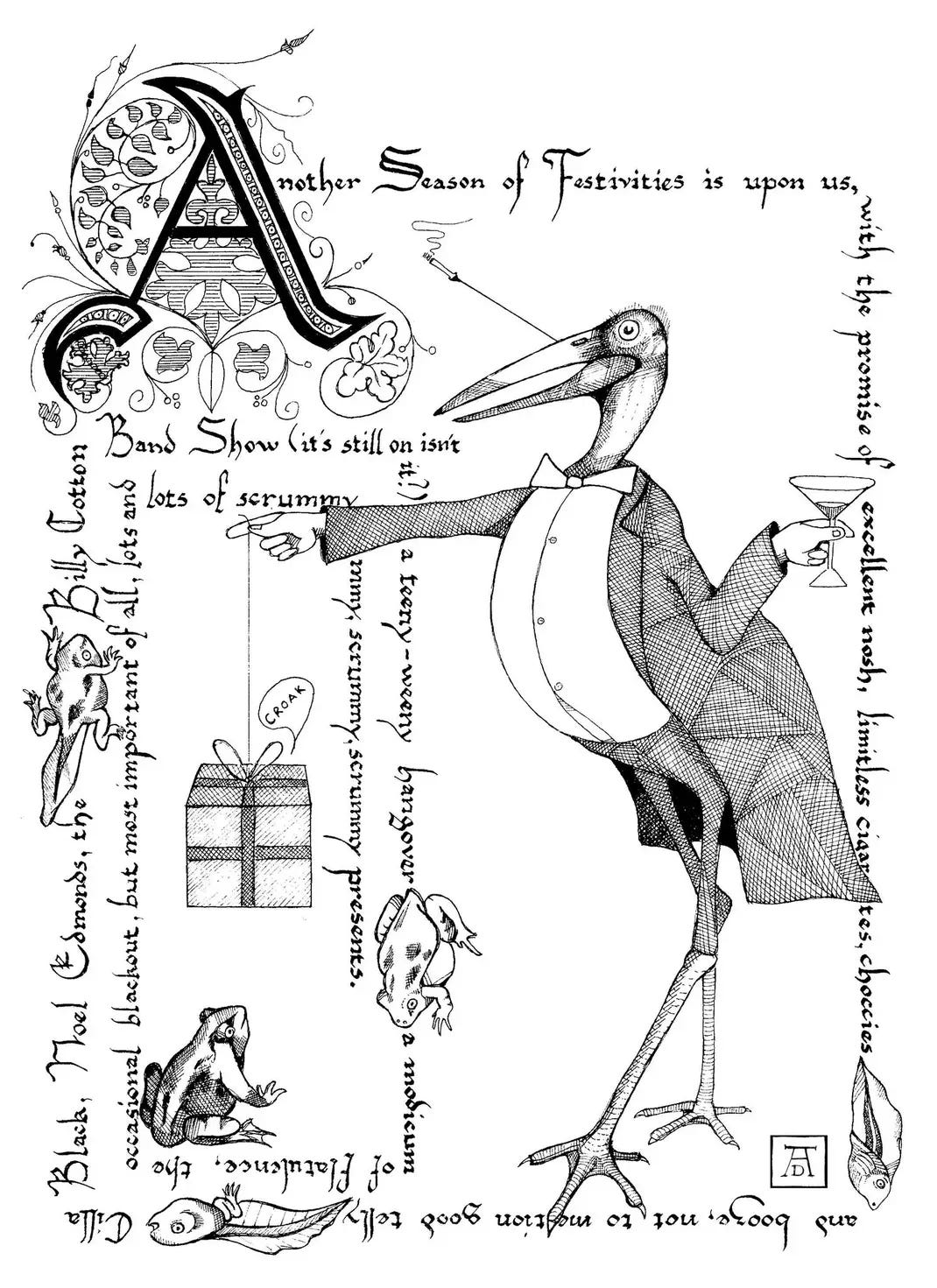

Randal Eldon Greene: You created some wonderful illustrations to go along with this book. Do you consider yourself an artist first or a writer?

Charlie Selkirk: Neither really.

I’m not really an artist, I simply doodle and draw cartoons which I suppose is a lower artform.

On the other hand, I really enjoy writing. That is, having an idea and then tapping it out on a keyboard. But I have a horror of drawing. I draw almost solely with a dip pen and Indian ink which involves very fine lines and hatching. I couldn’t have made it more difficult for myself. The dip pens inevitably end up blotting everywhere. At the end of doing extensive and intricate hatching, I usually end up smudging it. Why must it be like this? Why? Why?

From being a teenager I have only really drawn in dip pen and Indian ink which has resulted in many, many unfortunate accidents over the decades. I spilt ink all over my bedspread as a young boy, an accident in which I discovered how difficult it is to clean up Indian ink. I quickly got bored and realised that luckily there was quite a lot of black in the pattern of the bedspread and that it didn’t show up as badly as I first thought. My mother didn’t appear to have noticed but maybe more likely she had long given up on me in despair.

This has been a repeating theme throughout life.

A few weeks ago I was transferring Indian ink from a large bottle to a smaller, more manageable jar. I’d bought a rather elegant, well-sized pipette from Amazon to perform the task. I pushed the pipette into the bottle and pressed it to squeeze out the air in order to fill it with ink. To my innocent surprise a huge fountain of ink welled out of the bottle and went all over my drawing table. I seemed to have learned nothing. Once again it took a vast amount of time and quantities of kitchen towels to mop it up. I like having spontaneous doodles and practice attempts on my drawing table but I object to having it covered with one enormous, amorphous splodged black blob. Once again it took ages to remove it. But even now I can see its stain on the table which is dried on and immovable and displeases me immensely.

The one thing demonstrated beyond all doubt is that Indian ink never fades.

Randal Eldon Greene: Is there a place where those interested could find more of your artwork?

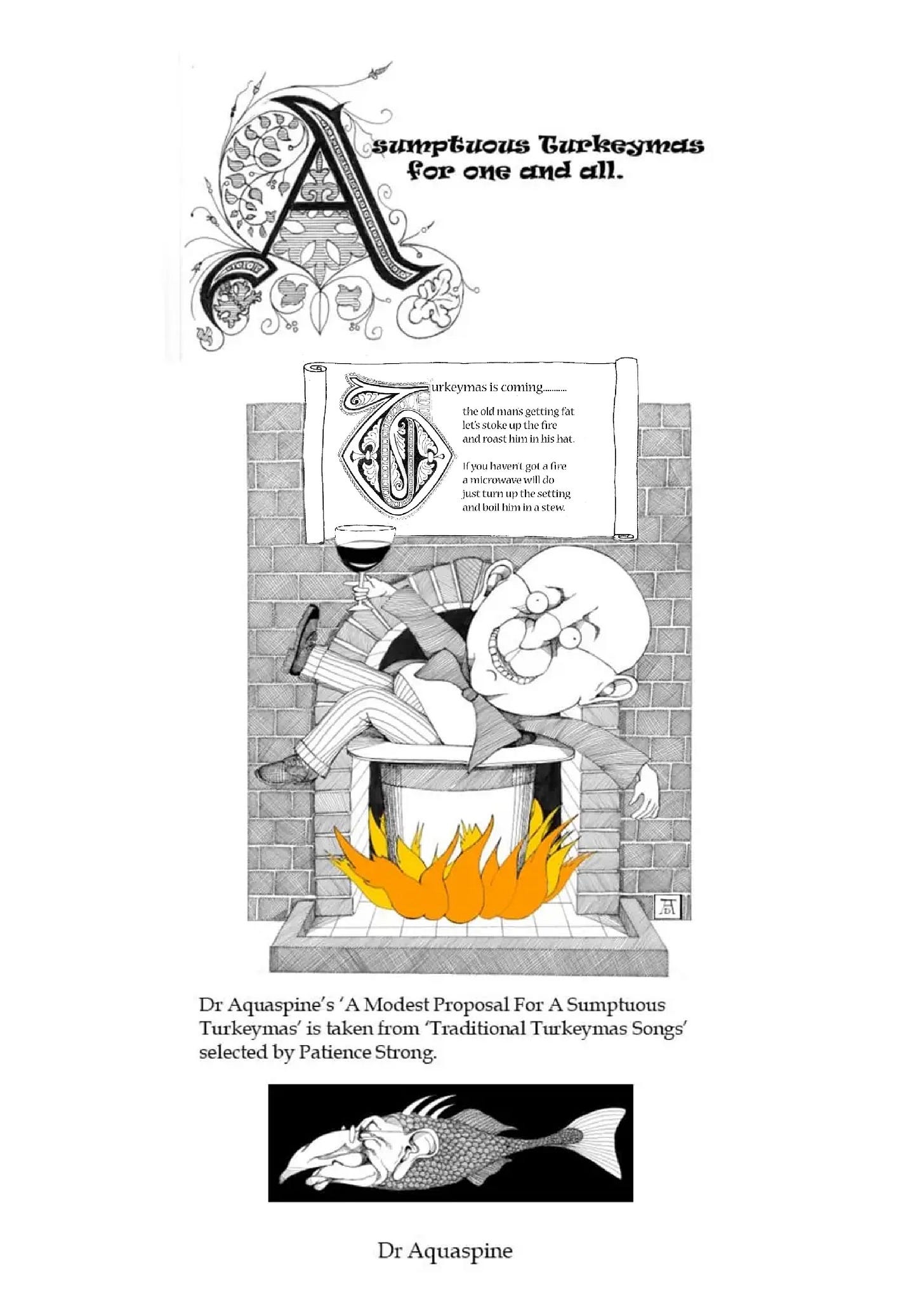

Charlie Selkirk: I’ve made two attempts at websites (both calledThe Black Art of Dr Aquaspine) but disliked both of them intensely. I could never work out what I hoped they would achieve so I removed them. There’s been recent talk of a new website.

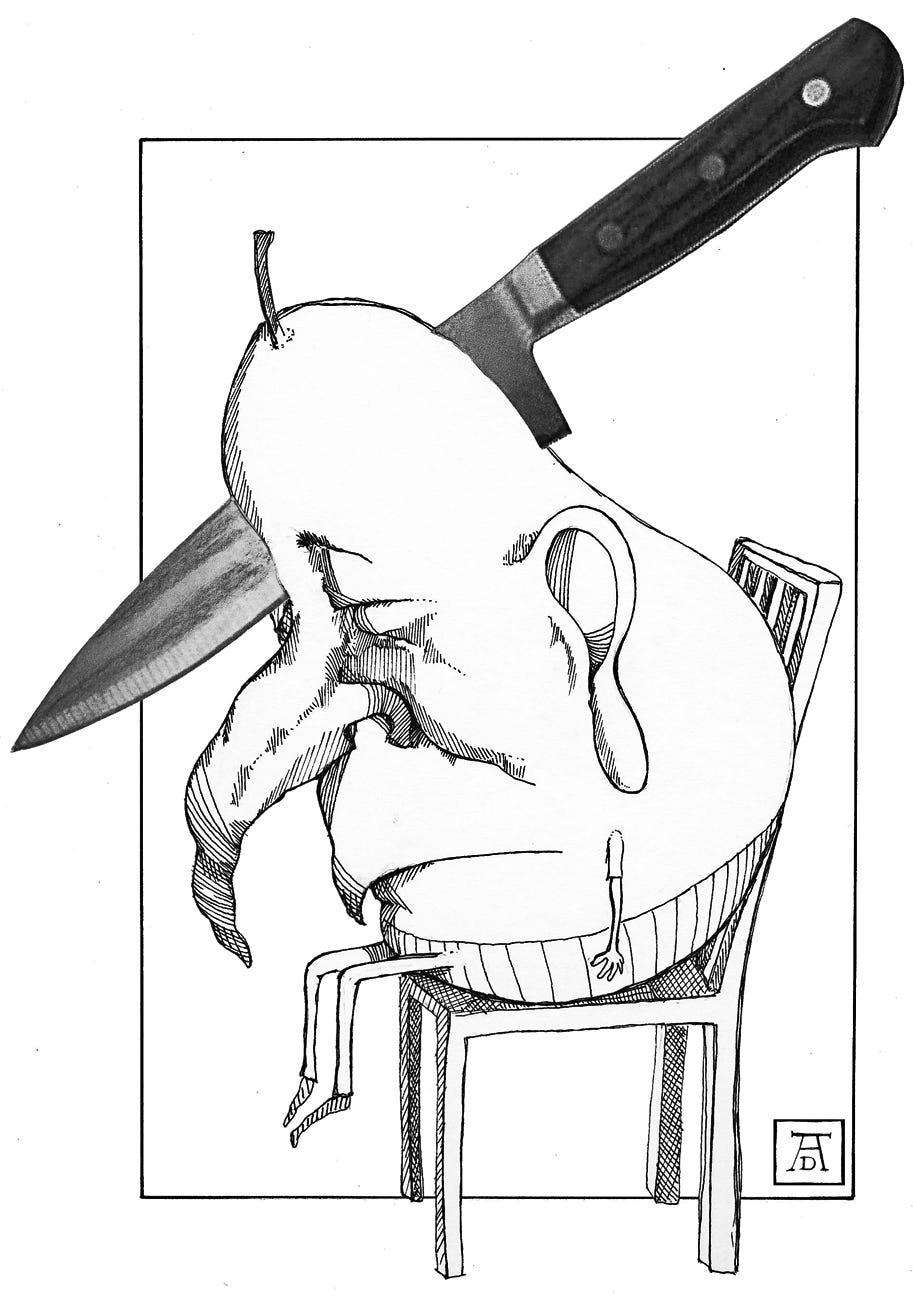

For quite a long time drawings and cards were exhibited and sold in a genteel Jewellery Shop in Bude in Cornwall. The display included some of the illustrations from the book and I always felt their vulgarity clashed unfortunately with the style of the shop. I fear the clash may have caused psychological damage. There was a small boy with his father examining the pear with a knife in its back.

‘But Daddy, the pear’s going to be alright. Isn’t it? The pear isn’t dead is it, Daddy?’

The father was optimistic.

‘No, no. The pear’s going to be fine.’

The pear isn’t going to be fine. The Pear is dead.

There is an excellent artist in South Devon called Simon Drew who sells cards which, at least superficially, resemble mine but with many differences. I use hatching to convey shading whereas Simon Drew uses stippling. Simon Drew’s style tends to be whimsical whereas mine, at times, can be unnecessarily nasty and certainly not the kind of material that should be displayed in a Jewellery Shop.

I remember a very nice little old lady walking in.

‘Ah good. I see you’ve got some Simon Drew.’

She went over and had a look. Her benevolent expression rapidly changed to disgust. Without speaking, she turned round and walked straight out of the shop.

Oh well.

I certainly envy Simon Drew’s industry and wish I could have produced even a fraction of his output.

Nothing lasts forever. The proprietor of the shop decided to become a publisher.

Randal Eldon Greene: “A Bird of Dereliction” is the title story for your collection. Of all of your stories, I think this is the one which could truly be taking place in our own reality. That is to say, it’s a story of madness. Or have I misread your stories, are they all tales of madness? Is it all a frolic through Alice’s nightmarish wonderland?

Charlie Selkirk: I think it would have been a bit of a cop out if it turned out that all the stories were a ‘frolic through Alice’s nightmarish wonderland’. A bit like if it all turned out to be a bad dream.

Thank you again for this unique experience.

I have very much enjoyed your charismatic and probing interview style.

It has been a great pleasure to meet you Randal.

Randal Eldon Greene: Likewise, Charlie. I’ll be staying in touch.

A Bird of Dereliction on Amazon.

© 2023

About the interviewer:

Randal Eldon Greene is the author of Descriptions of Heaven, a novella about a linguist, a lake monster, and the looming shadow of death.

His Instagram is @RandalEldon Greene

His website is AuthorGreene.com

You can also support our work by buying cool merch like mugs and t-shirts.