Interview with Caroline Miley - 2021

Interview #8 (fiction, historical fiction, literary fiction, political fiction, novel)

Caroline Miley is an art historian and writer with a long-time passion for art, history and literature. She is fascinated by the late Georgian era, a time when the old and the new existed side by side in an era of rapid transition. Society was in flux; new worlds were being mapped in the heavens as well as on the planet; Europe was in the grip of revolution; anything seemed possible. Miley writes novels that explore this wonderful time.

Randal Eldon Greene: Hello, Caroline Miley,

Your novel The Competition is about a London painter in the Georgian period. You're an art historian, so I think you'd be pretty qualified to give us an artist's story from about any era of of history. What about this period did you find compelling enough to create a story around the painter Edwar Armiger?

Caroline Miley: Hello Randal.

I find the late Georgian era fascinating for a number of reasons, but the main one is that it stands on the border of the old world and the new. It was a time of enormous change. There were many people who were still living a way of life that had not changed a great deal for centuries, farming the land in the same sorts of ways, rarely moving far from home, some still believing in witches and magic, many uneducated. At the same time, it was an era of exploration and discovery and massive expansion of knowledge in all sorts of fields - new planets, new countries, new scientific theories. And in society - it’s thought of as very genteel, but it still retained the rambuctiousness of the Georgians. It was a lot freer and easier than the Victorian era that followed. The King had a mistress - or several. Men drank incredible amounts. There was a lot of gambling, driving fast, living a rakish life. The clothes reflect this - light dresses for women and riding boots for the men. Their hairstyles too - ruffled, 'natural' - none of the powdered wigs of their fathers or the neat coiffures of Victorian ladies. So, a very interesting time to be alive.

Randal Eldon Greene: You provide many fascinating details about the often elaborate process of painting. Are these just things you know or were you collecting these details over time for a project like this book?

Caroline Miley: I’ve always loved art. I’m an art historian and spent much of my life teaching in an art school, so I had plenty of opportunity to see artists at work and understand the life of an artist. I’ve also done some painting and drawing myself and was interested in techniques and methods. For the book, I did a lot of research specifically into the techniques in use at the time to add to my general knowledge. I knew an artist who ground his own colours in the traditional way and watched him work, just as artists had been doing for centuries. I wanted to convey the real feel of being an artist then, especially since new techniques and pigments were becoming available to extend methods that had been around for ever. New yellows, for instance, that Turner was keen on.

Randal Eldon Greene: The feel of being a working artist in the Georgian period certainly came through. Yet I felt in tune with your character, despite the two hundred year gap between us. The times Edward is tempted to put off painting "for some ale and conversation," how he'll walk to clear his mind, and his realization that "all we artists were putting ourselves up for examination" felt so true to my own experiences — and I'm not a painter but a writer. Did you imbue Edward with some of the realities of your workaday life as a writer or did you create such a true portrait from a pastiche of working artists you've known?

Caroline Miley: I’m glad it felt true - that was my aim. I suppose it was a combination of how I know artists live and work now - and I’m sure it was the same then - and my own experience of life, and life as a writer, as you say. When I’m writing, I try to immerse myself in the character’s world, then imagine how I’d feel and behave in that situation if I were that character. Then at least it feels true to me, and I hope to readers. If it doesn’t feel true to me, I can’t hope that it’d feel true to my readers.

One of the aspects I like about writing historical fiction is that I think people are pretty much the same, throughout history and across cultures. For instance, you can read Pepys saying, four hundred years ago: ‘put on my new laced suit for the first time today. Looked very well in it. I pray God make me able to pay for it’ and laugh out loud. But at the same time, their way of life and values and ideas may be very different - the concepts of honour and duty, for instance, that were very important in 1800, have changed a great deal. Social expectations around relationships between people. So I have to imagine myself as a person like me, but with those different values. That’s the part I like most about writing, I think.

Randal Eldon Greene: There are really three strands of plot interwoven to create your novel. There is the painting competition of the title. There's also a romance plot that has some unexpected twists in it. The third strand is a political one: the worker fighting for his rights – the inevitable kind of tension created by capitalism. I'm of course familiar with the Luddites, but for the audience that might not be, do explain this part of history and tell us why you decided to draw your character into this political movement.

Carlone Miley: The Industrial Revolution and the situation of workers was in my mind from the start. The genesis of the book was: I had been thinking of writing about the social and industrial history of the era and the huge changes it introduced to the nature of work, and also a book about the life of an artist at the time. Then I suddenly saw how I could combine them. I’ve been interested in the history of work and workers’ movement for a long time, and the Luddites were a key moment at the beginning of this struggle, which goes on today.

The Luddites have a bad press, associated with simply being old-fashioned and unwilling to accept new technology. However, they were astute, politically educated, skilled tradesmen, which I’ve tried to show in the character of Thwaite. These were people who were highly skilled in traditional industries, mainly in cloth production, and who had their own businesses. They saw the new machines come in, which were specifically introduced by factory owners to replace workers, and the cloth workers saw clearly that this was the end of their trades, skills and their employment, and the employment of their children and children’s children, for ever. They were 100% correct. These men had no votes, no political power, and no influence. They made representations to Parliament, but Parliament consisted of wealthy land-owners and factory-owners, who opposed them. So in desperation they took to smashing the machines.

It’s important to understand the background. This was just after the French Revolution and the overthrow of the ruling class in France. There was a lot of writing about ’The Rights of Man’ by authors and activists such as Thomas Paine, who would have been arrested if he’d set foot in England, William Cobbett and others. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote ’The Rights of Women’. There were also food shortages and outright famine, and protests were put down violently by soldiers. So a very interesting time in turmoil.

The ‘Competition’ of the title is the competition of life, the struggle to make a life and to get ahead, and people have to decide what they can do in the situation they’re in. And I don’t think it’s any different today. I hope people would see that the struggles of Thwaite with mass unemployment of skilled workers due to technological advance, is the same now.

It’s popular today to think of artists as free spirits, but they’re just as bound by the dictates of the art world as Edward was.

Randal Eldon Greene: I was fascinated by the tensions you showed through many of the artists in The Competition as they attempted to navigate their own visions of great art and the expectations of the gatekeepers who either directly hired the artists or set the standards of "good taste" such as the Royal Academy. Today we tend to think of artists as completely free spirits, but you show this to not have historically been the case

Caroline Miley: Things certainly have changed a great deal in the art world. This change in the artist’s self-perception happened through the development of Romanticism, which posited for the first time the artist as a person uniquely gifted with sensitivity and creativity, who saw and could interpret the world in a special way denied to other, more mundane souls. This trope was incorporated into Modernism, which discarded so much else of the past. In Edward’s time artists saw themselves traditionally, as skilled artisans who had the ability to portray and express concepts and the physical world, although they were gentlemen, not tradesmen. The Royal Academy and like institutions elsewhere helped raise the status of artists. But artists would never have thought of art as a means of self-expression or self-actualisation as we do today.

It’s popular today to think of artists as free spirits, but they’re just as bound by the dictates of the art world as Edward was. It’s ironic but true. The late great Peter Fuller once remarked that true radicalism in art today would be to paint watercolours of flowers (or something along those lines). Because when everyone is creating dystopian videos or sharks in tanks, obviously doing that is just conforming to the ‘Academy’. Today that’s run by critics and galleries, but it’s the Academy, all the same.

In Edward’s day, artists, patrons and the Academy were pretty much all on the same page about what constituted art, and great art. Edward discusses this in his critique of the actual RA exhibition of 1812. The Academy was not opposed to innovation - Turner in his day was widely admired, for instance, and taught at the Academy Schools. That’s because it was run by artists, unlike the French Salon, which was run by the government. The Academies and the canons of taste did produce a great deal of formulaic, mediocre art, but that’s true today too - worse, really, because in those days a basic level of technical skill was the bottom line, so mediocre artists could at any rate produce pretty landscapes, vases of flowers, etc., which were easy on the eye. Great artists like Lawrence, Raeburn, Turner, and Constable did as they wished.

Edward’s dilemma was that the art he wanted to make was not fashionable. The book’s a journey of him trying to work out what he wants to do, and whether he has the nerve to do what has meaning for him at risk to his career and income. I see that as a universal dilemma, as true now as then. So the theme of the book is really ‘what constitutes success, and what should you do to get it?’ Some of his colleagues, like Quayle, are more than happy to more or less milk the system. He’s a good painter, perhaps very good, but unlike Edward, he has no personal ambition to do something meaningful. His ambition is to be successful in society’s terms, and he puts his efforts into that, shrewdly assessing the market and developing an upmarket clientele. There are plenty of Quayles around today. It’s the Edwards who are rare at any time.

Randal Eldon Greene: What's the next artistic project for you? Another book or something else?

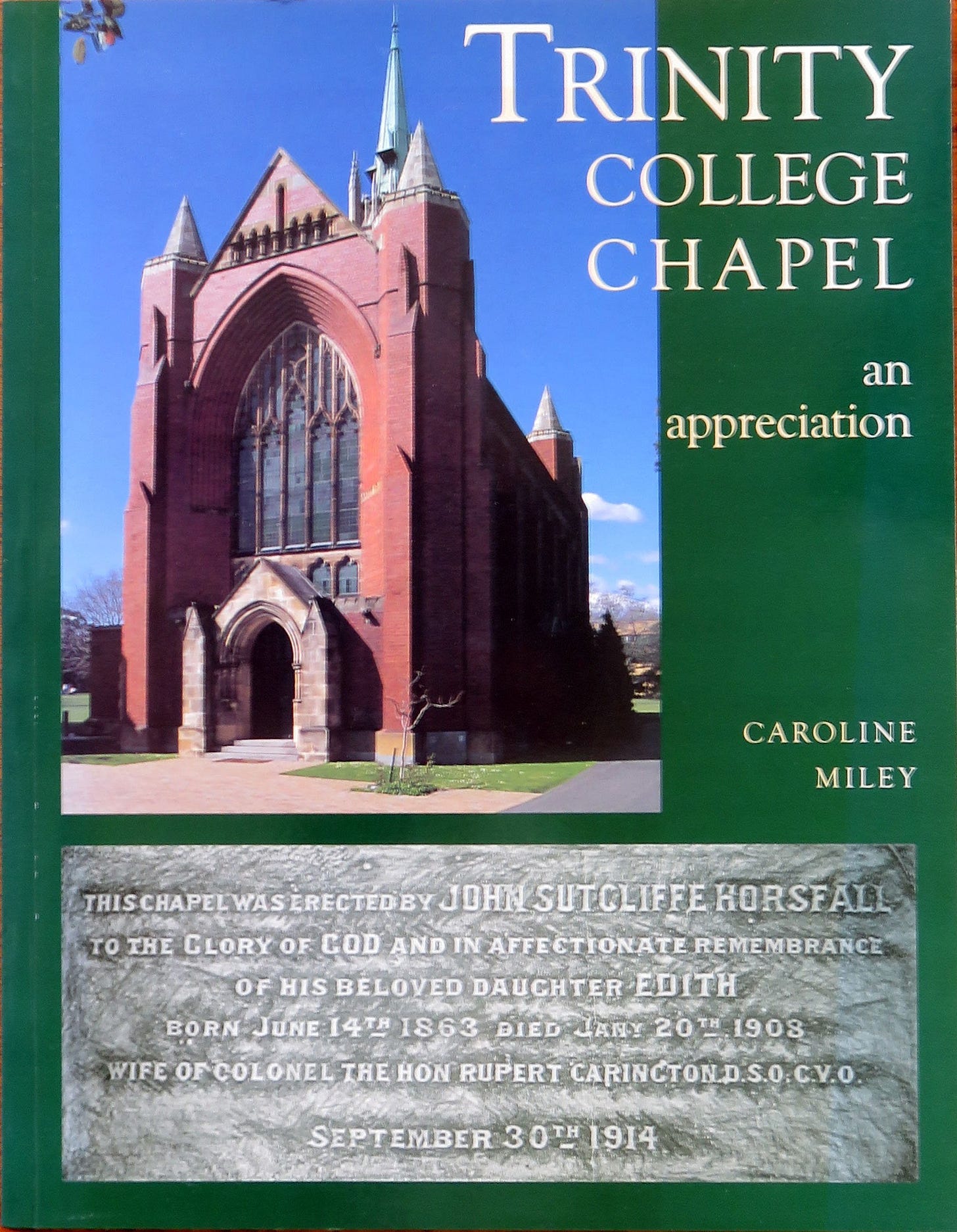

Caroline Miley: I’ve just completed an art history book, a catalogue raisonné of the Australian stained glass artist Christian Waller. Now I plan to return to a historical novel that I had started earlier, a work based around the campaign to abolish the slave trade in the early 19th century. It also looks at the condition of women at the time. It’s quite hard to get back to it after working on non-fiction, and it’ll be a very different book. My thinking about it has evolved significantly. I’d like to expand my writing style, too.

Randal Eldon Greene: Those are wonderful writing goals. I look forward to reading more of your novels. Thank you so much for your time, Caroline.

Caroline Miley: Thanks for the interview, Randal. Much appreciated.

Purchase The Competition on Amazon

© 2021

About the interviewer:

Randal Eldon Greene is the author of Descriptions of Heaven, a novella about a linguist, a lake monster, and the looming shadow of death. His typos are tweeted @AuthorGreene and his website is AuthorGreene.com